Poetic dispatches from the Dacian Limes

Team MAPPOLA (Chiara Cenati, Alexander Gangoly, Victoria González Berdús, Tina Hobel, Peter Kruschwitz, Denisa Murzea, Mirko Tasso) report on their first epigraphical expedition. A Romanian version of this piece has originally been published in Limes: Frontierele imperiului Roman în România (10 (2021) 15–21, open access version available here). We thank the editors, Felix Marcu and George Cupcea, both for the publication of our report and for their kind permission to re-publish this text here in English.

Introduction

Poetry and music were essential parts of cultural practice in the Roman empire, providing cultural coherence across its society at large, but also giving very specific identities to its constituent communities. Yet, when we learn about Roman poetry, we usually restrict our view to a very small number of classical authors, from a narrow timeframe and all with a special relationship to the city of Rome and its ruling class. The MAPPOLA project’s ambition is to transform and to democratise our understanding of Roman poetry. We expand the established canon and diversify the ancient poetic voices through our study of the Latin and Greek verse inscriptions of imperial times. The quantity of the material spread across the vast extent of the Roman Empire – we are talking several thousand texts here! – allows us to investigate the regional and ethnic differences of the epigraphic and poetic habits. This entails a radical shift away from a small canon of texts produced and consumed by the elites, focusing on the poetic thoughts and artistic ambitions of people from significantly lower social standing, from all runs of life, and from all parts of the empire.

A particularly important and interesting aspect of our investigations is the examination of emerging and transforming poetic habits in the provinces and the borders and frontiers of the Roman empire. In this context, Team MAPPOLA has begun to study the production of verse inscriptions in Roman Dacia. Being able personally to inspect the actual monuments that carry the poems is of the greatest importance to us. During an autopsy campaign to Dacia in July 2021, we were able to identify important additions to the already known number of poetic pieces from that region, raising the total number of verse inscriptions from this province to almost 30. The variety in the typology of texts, their dedicants, contexts, and occasions is truly stunning and differs from any other Roman province. One particularly striking example for that are the character and (comparatively high) number of votive verse inscriptions for which there would appear to be no parallel in other parts of the empire (see, for example, the famous inscription dedicated to the Nymphs which was found in Germisara).

One of the traits that characterise the presence of Roman culture in the Empire is the diffusion of inscribed Latin and Greek poetry. Along the limes, first forms of epigraphic poetry appear at around the same time as military occupation: in other words, poetry, specifically inscribed poetry, literally arrived in the legionaries’ knapsacks. However, the spread of epigraphic poetry in the provinces, and especially along the frontier, is by no means a homogeneous phenomenon: all regions and centres carry their own, individual, highly specific poetical fingerprints, depending on local preferences, linguistic substrates, social contexts, and many other factors.

It is on the frontier especially, however, where we see some of the most interesting manifestations of what de facto is one of the earliests and cheapest forms of Roman art in the province. The authors of these verse inscriptions created art, verbal art, by putting into words their life experiences and collective imagery. To give an idea of what our team is working on, we have selected three verse inscriptions from the Dacian limes area. The editions of the texts, as well as the translations, are our own.

The veteran

[D(is) M(anibus?)]

Publi Aeli Ulpi vet(erani) ex dec(urione).

Hanc sedem longo placuit sacrare labori,

hanc requiem, fessos tandem qua conderet artus

Ulpius emeritis longaevi muneris annis.

Ipse suo curam titulo dedit, ipse sepulcri

arbiter hospitium membris fatoque paravit.

[To the Spirits of the Departed of ?] Publius Aelius Ulpius, veteran and former decurion.

He chose to dedicate this place to long, hard work, this resting place, where he would finally bury his tired limbs, Ulpius, after completing years of long-term service. He himself took care of his own epitaph, he himself, as responsible for his grave, arranged a dwelling for his body and his destiny.

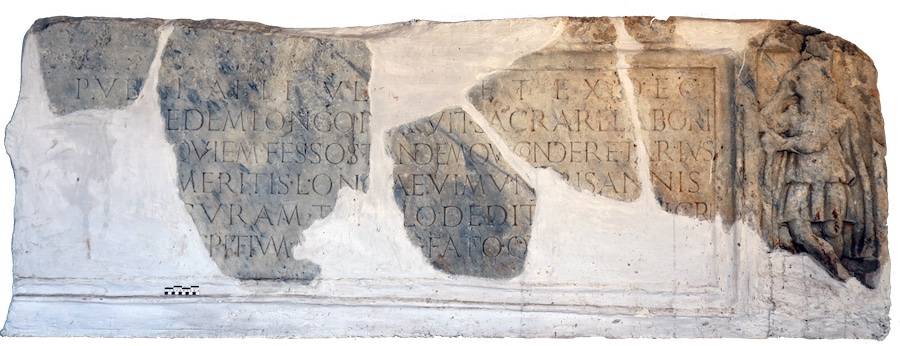

Once a large sarcophagus, this monument from Tibiscum has been (partially) reassembled from five fragments. The inscribed area, surrounded by a frame, was originally flanked by two figures; today only the representation of Attis, on the right, is preserved. The text is beautifully engraved, and guidelines as well as traces of colour are still visible.

The first preserved line contains the name of the deceased and his identification as a veteran and former principalis of the Roman army. The remaining lines (2-6) form a poem, which consists of five hexameters. Each verse of the poetic composition occupies exactly one line. In order to accommodate the verses, graphic resources like ligatures were employed. This particular feature shows that the stonecutter (who is not the author of the poem, as the text clearly reveals) was aware of the poetic content of the text.

The retired soldier P. Aelius Ulpius lived around the middle of the second century, as his name clearly reveals. He was a new Roman citizen, son of a peregrinus who had received Roman citizenship, or a peregrinus himself, who made his way into Roman society through his service in the army. In the Roman army he also managed to make a career, reaching the grade of decurio in one of the auxiliary units active at Tibiscum. While the name of the unit was apparently deemed irrelevant by Ulpius, and therefore omitted, it is essential for him to emphasise his status as a veteran, who had achieved the honesta missio, the biggest reason for pride for a Roman soldier. The theme of the veteran who successfully concluded his service is palpable throughout the poem: after long years of hardship and efforts, Ulpius was finally able to rest in a rich grave, for which he – as he stresses in the poem – had paid himself. This grave was, in fact, a lavish, beautifully decorated sarcophagus set in a mausoleum. We don’t know where exactly Ulpius was born, but after the end of the military service he had decided to settle in Tibiscum, which had become his new home and the place where he wanted to be remembered. His new identity, transformed by having become a full Roman citizen, is not only clarified through the mention of honourable service in the army, but also by the very use of a Latin poem, ensuring for himself an everlasting memory.

Bibliography: CIL III 1552 = CIL III 8001; CLE 460; IDR III/1, 157; Sămărghitan 2003, 174-175, nr. 6; HD046529; F. und O. Harl, Ubi Erat Lupa, http://lupa.at/17549

The girl

D(is) M(anibus).

Aelia Hygia vixit

annos XVIII

Ael(ius) Valent[inus dec(urio)?]

col(oniae) Apul(ensis) fl(amen)

libertae et coniugi

gratae,

quam tempus durum

rapuit familiam=

quae (!) simul. Dacia te

voluit, possedit

Micia secum. Have,

puella, multum adque (!)

in aevum vale.

To the Spirits of the Departed.

Aelia Hygia lived 18 years. Aelius Valentinus, decurio of colonia (Aurelia) Apulensis, flamen (put this monument) for his freedwoman and dear wife, whom a hard time snatched away, together with the family. Dacia wanted you, Micia holds you. Greetings, girl, many times and forever farewell.

Originally, this verse inscription comes from Micia. Today, however, it is kept in the Reformed Church of Mintia (Hunedoara). More precisely still, the monument was inserted into the interior pavement of the church, being reused as a construction material. In the process, the upper part (exhibiting a relief) and the lower part of the stone were mutilated. What is left of the andesite stele (155 x 80 cm) is broken into two parts two, resulting in the loss of two lines of text.

The text of the inscription, displaying many ligatures, is surrounded by a moulded frame, decorated with kymatia. Moreover, the letters were cut rather carelessly; the composition itself, however, is one of great value. The first lines (1-5) are written in prose, and they introduce one Aelia Hygia, a girl of only eighteen years who is commemorated by her husband, Aelius Valentinus. The remaining lines (6-14) form the poem consisting of a total of four verses.

In this fascinating composition, there is a striking and rather unusual alternation of rhythms. Each verse expresses a specific idea that is introduced in a metrical scheme markedly different from the surrounding text. The first verse is largely hexametrical in its rhythm, and it introduces the role and social status of Aelia Hygia, a dear freedwoman and wife. With the second verse, in which Aelia Hygia’s and her family’s sudden death is recorded („whom a hard time snatched away, and at the same time the family”), the metrical scheme changes radically into an iambic senarius. Subsequently, the third verse, reverting back to the previous rhythm of a dactylic hexameter, introduces yet another idea: Aelia Hygia, as a migrant, was very welcomed in the province of Dacia, but it was the settlement of Micia that has taken possession of Aelia for herself. Finally, in the last verse, a farewell to the deceased, the rhythm changes back to that of an iambic trimeter.

The poem speaks in an impersonal, third-person voice about the short-lived existence of Aelia Hygia and about the sense of belonging as well as about how a foreigner might arrive and find their place within a new society and family. Aelia Hygia was a migrant of unknown origin, but is presented as warmly welcomed in Dacia („Dacia wanted you”). There she had the chance to create a new home, even in death, her body being forever in the grounds of Micia. And yet, as the tone of the poem is impersonal, one must wonder if this was really the life that Aelia wished to have – whether she truly wanted to remain in Micia forever. In any case, this poem offers us important information, beautifully wrapped into verbal artifice, about a real life in the province of Dacia as well as about the way in which people from Dacia engaged in, and with, this form of cultural expression – the creation of inscribed verse -, of family networks and migration.

Bibliography: CIL III 7868 = IDR III/03.159 = CLE 1558; Sămărghitan 2003, 180-181, nr. 12; HD045444; F. und O. Harl, Ubi Erat Lupa, http://lupa.at/11797

An anonymous reflection on life and death

D(is) M(anibus).

Tu qui reciprocam se=

mitam voto subis,

morare paulum, vitam

cognoscis tuam.

Hic sumus expositi, mor=

talia munera functi

[- – -]++[- – -]ES

– – – – – –

To the Spirits of the Departed.

You, who walk back and forth a path because of a vow, rest a little: you know your life. Here we are exposed after having fulfilled our mortal duties (…)

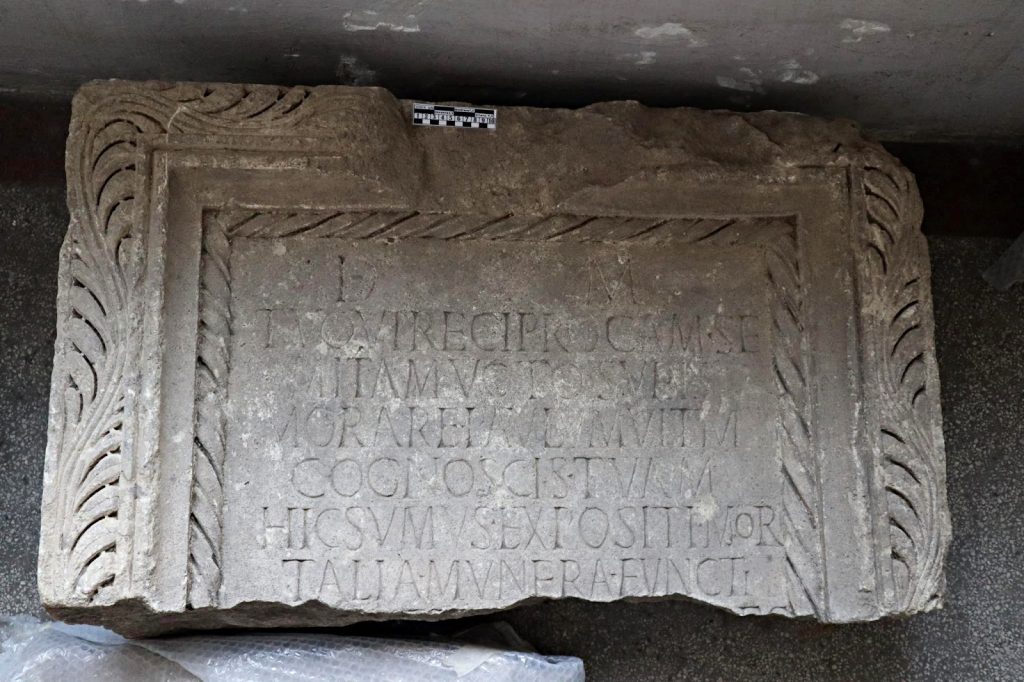

As a last example of Dacian poetry we have chosen a text that draws us straight into the everyday life of Roman Napoca of the first half of the 3rd century A. D. The object itself is a white limestone slab of relatively big dimensions (64 x 102 x 24,5). The surviving fragment once formed the upper section of the monument. As is visible on the picture, the inscription was surrounded by a moulded frame with vegetal motifs, a section of which is missing at the top. The decoration continues on the two sides of the piece, which shows that originally it was not embedded into a wall, but visible. At the very top of the piece, to the left and right corners there are two clamp holes. The piece was discovered in 1987 in cimitirul roman târziu din Piața Cipariu în poziție secundară, which could explain the clamp holes.

The text was inscribed in very regular square capitals. In total, there are eight preserved lines, all of them aligned to the center of the epigraphic field. The careful and thought-out layout is also reflected in the verse distribution: after the dedication to the Spirits of the Departed, each of them spreads across two lines, the second one always a bit indented. The total absence of personal information leads us to believe that this would have been included at the end of the inscription, probably in the form of a prose subscriptum.

The composition opens with what at first would appear to be the typical address to the wayfarer, inviting them to stop and read, written in two iambic senarii. Yet, here this familiar trope finds a detailed and striking form that is without parallel in the Roman Empire. Might the author of the text have had in mind the specific location and surroundings of the monument when he was composing it? At the same time, the expression is also metaphorical and, therefore, universal: life is a path that the living walk up and down carelessly. Precisely because of this, the poetic voice asks the traveller to stall their step (morare paulum, adding, rather mysteriously: vitam cognoscis tuam. Whether this is a call to self-reflection (‘you know your own life’) or an invitation to read about the destiny that awaits us all (‘here you will recognise your life’, with cognoscis employed pro futuro, or even written instead of cognosces), the reader has been reeled into a conversation with the monument. With the beginning of the last preserved verse (hic sumus expositi…) the tone changes significantly together with the rhythm, moving from iambic senarii to a dactylic hexameter. Here we start to get a glimpse into the life(s) of the deceased, which is sadly cut short by the breakage of the piece.

Bibliography: ILD 565 = CERom-19/20, 863 = Ardevan – Hica, Acta Musei Napocensis 37, 1, 2000, 243 Nr. 1 = Sămărghitan 2003, 172, nr. 3; F. und O. Harl, Ubi Erat Lupa, http://lupa.at/15113; EDH https://edh-www.adw.uni-heidelberg.de/edh/inschrift/HD043650.

Conclusion

As always in the area of epigraphy, monuments and texts raise many more questions than one may possibly answer. Identities and backgrounds remain obscure, and we only get to see what the respective authors wanted us to see. Poetic inscriptions, however, are more talkative than their prose counterparts, and they give shape, form, and imagery to the people that are commemorated in these monuments, and we learn about their perception of life and death, about their fears, worries, dreams, and happiness. At the same time, and in a more holistic view, we begin to understand the degree to which epigraphic poetry was not only an ever-present element in everyday life even at the Dacian limes, but also a culturally highly significant outlet of artistic ambitions, from the creation of striking images to sophisticated changes of rhythms and tunes. The Dacian limes and the societies that populated the area may have been far away from the city of Rome and the seemingly so sophisticated lives of its elites: this did not, however, mean that they lived without music and poetry, or that they were unable to give an artistic shape to their hopes, dreams, and fears.

Bibliography:

CIL = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, Berlin, 1862–.

CLE = F. Bücheler, E. Lommatzsch, Anthologia Latina. Pars Posterior: Carmina Latina Epigraphica, Leipzig 1895–1926.

IDR III 1 = I. I. Russu, Inscripțiile Daciei Romane III. Dacia Superior 1 (zona de sud-vest), București 1977.

IDR III 3 = I. I. Russu, Inscripțiile Daciei Romane III. Dacia Superior 3 (zona centrală), București 1984.

ILD = C. C. Petolescu, Inscripțiile latine din Dacia, București 2005.

R. Ardevan, I. Hica, ‘Inscriptions de Napoca’, AMN 37/1, Cluj-Napoca 2000, pp. 243–252.

C. C. Petolescu, ‘Cronica epigrafică a României (XIX-XX, 1999-2000)’, SCIVA 52/53, București 2001/02, pp. 267–300.

A. Sămărghitan, ‘Poezia funerară în Dacia’, în M. Bărbulescu (ed.), Funeraria Dacoromana. Arheologia funerară a Daciei romane, Cluj-Napoca 2003, pp. 170–195.