Dulce et decorum est de mortuis recordari: it is sweet and fitting to remember the dead

With the Epigram of the Month November, we are delighted to welcome our doctoral researcher Mirko Tasso as the most recent addition to Team MAPPOLA.

The commemoration of the dead in Liguria, my homeland, has ancient roots, and, ever since it was standardized, the annual celebration dedicated to them on 2nd November, the month of November itself, like in many other countries, has become the month of the dead par excellence. Over the course of the centuries, several traditions have accompanied All Souls’ Day, and the whole month of November, in the region of Liguria.

Still strong, though not exclusively Ligurian, is the custom of visiting the tombs of relatives and friends within the first eleven days of the month, up to St. Martin’s day, and the same dead were once believed to visit their families’ houses during the nights of this period.

Perhaps rather less common to other parts of the world, very precise receipts for foodstuffs are historically associated to the celebration of the dead in Liguria.

The typical dish on All Souls’ Day, especially in the Genoese area, is stocchefisce e bacilli, stockfish with fava beans. In fact, the dish is so popular that it has resulted in the proverb “a-i Morti, bacilli e stocchefisce no gh’è câ che no i condisce” (“On All Souls’ Day, there is no house in which stockfish with fava beans is not seasoned). It is perfectly likely that the origins of this traditional meal go back to a tradition that both links fava beans to mourning, due to their dark appearance, and that associates the stockfish to penitence.

A popular dessert to accompany the stocchefisce e bacilli is the so-called castagnasso, a pie made of pine nuts, raisin, and flour of chestnuts – and it is this last ingredient that is also historically associated with death: there used to be a tradition, now in decline, that saw grandmothers buying, or preparing by themselves, long necklaces of boiled chestnuts and apples, the so-called raeste, for their grandchildren. Such necklaces may well have been conceived of as quasi-rosaries, and thus they combined a didactic purpose with a tasty benefit (since they were, of course, eaten during mass on the eve of All Souls’ Day!) – teaching children the importance of remembering and honouring the dead.

The most traditional, easily recognisable, and characteristic custom of commemorating the dead in Liguria, however, especially in Tigullio, was the preparation and the lighting of the offiçiêu – long white or coloured wax candles, manufactured with remarkable precision and wrapped around wooden shapes in order to create small books, shoes, hats, baskets or wicker wine bottles.

It was especially the children that got all excited when looking at these miniatures, and, according to the tradition, they were designed to be lit and then to be brought with them to their respective churches on occasion of the masses held for the dead, or, alternatively, be lit in private homes during the prayer of the rosary recited by the entire family for their dead relatives on All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day.

These colorful candles, too, however, accompanied by poems, have seen a sharp decline since the 1970s: perhaps it was just too difficult and laborious to prepare them, and too cumbersome to remove their wax spillage from the floor after the celebration. By now, they have disappeared almost entirely: essentially, nowadays offiçiêu only survive in the memories of older generations who lived through their childhood before the seventies, and who – like my uncle, for example – are often unable to hold back their tears and sighs when they remember those pieces of art alongside an entire universe of traditions (and the individuals who are forever linked to them in their minds).

Regrettably, the flames of these candles were extinguished by the cold breath of the humanum tempus, a force that, as Ovid said two millennia ago, will devour everyone and everything (Ov. met. 15.234).

Despite the fleeting nature of all things, however, as well the cruel power of a tempus edax, humankind has always tried to escape cosmic nothingness and the shadows of oblivion. The same desire was shared by monarchs, clergymen, and artists who, by means of constructing magnificent monuments or producing superb pieces of art, tried to commit their own names to eternity. Yet, also the less affluent and powerful, of course, as well as the poor, despite their comparatively slender means, pondered and used the opportunities of leaving a material trace of themselves to posterity, in their desire to triumph over the sands of time.

To remain in Liguria, and specifically in Genoa, perhaps the clearest sign of this innate human desire is the famous tomb and epitaph of one Caterina Campodonico that can be found in the renowned Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno.

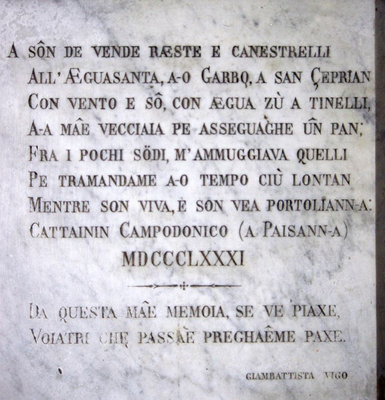

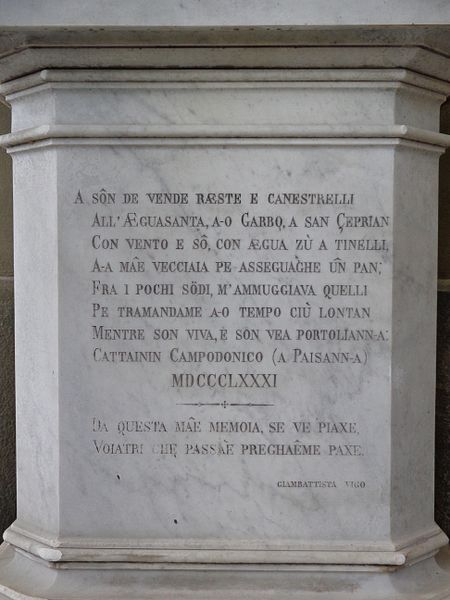

Caterina was born in 1804 to a very poor Genoese family, and, semi-literate, she started working as haberdasher to make a living, selling necklaces of nuts (raeste) and biscuits at fairs and village feasts. Separated from her drunkard husband Giovanni, her life turned out to be rather different from the ideals and imaginations of the local nineteenth-century society, causing a great scandal for her family and the ‘right-thinking’ people of her community, since she continued to work as haberdasher and to live independently. Close to the time of her death in 1882, Caterina had saved up enough money from her working life to be able to invest her money in a spectacular marble tomb in Staglieno. Caterina, in her desire to be eternally remembered, commissioned a monument from Lorenzo Orengo, and she had it inscribed with the following epitaph, in Genoese, written in elegant hendecasyllables by the poet Giambattista Vigo:

A sôn de vende raeste e canestrelli

All’Aeguasanta, a-o Garbo, a San Çeprian

Con vento e sô, con aegua zù a tinelli,

A-a mâe vecciaia pe asseguaghe ûn pan,

Fra i pochi södi, m’ammuggiava quelli

Pe tramandame a-o tempo ciù lontan

Mentre son viva, e son vea portoliann-a.

Cattainin Campodonico (a Paisann-a)

MDCCCLXXXI

In questa mâe memoia, se ve piaxe

Voiatri che passae preghâeme paxe.

By continuing to sell necklaces of nuts and canestrelli in the districts of Aquasanta, Garbo and St. Cyprian, in wind, sun, or strong rain, to win a loaf of bread for my old age, from a meagre fortune I saved up enough money to commit my name to the time to come, while I am still alive and I am a true inhabitant of Portoria district.

Caterina Campodonico (the countrywoman), 1881.

In this memory of mine, if it pleases you who passes here, may you pray for peace for me.

The verse epitaph has a double purpose: first, it records Caterina’s eventful life; secondly, and more importantly, it is a tool that, to Caterina’s mind, would ensure her eternity. Furthermore, as corollary to the poem in this function, there is also the tomb itself, which very obviously and faithfully represents Caterina in the way she would have been seen in her community during her lifetime, dressed with a lace apron and with a necklace of nuts, the source of her income and social independence, clutched in her hands like a rosary. Finally, and essential to guarantee immortality to Caterina, is the involvement of the passers-by, who are implored to behold the tomb and to read the epitaph while praying for peace for the woman and thus transmitting her name to future generations.

Caterina’s example, due to the magnificence of the burial and her complex story, is really remarkable. But also in ancient times the poor and marginalised managed to leave signs of their existences to posterity, and not rarely they did so by means inscribed verse epitaphs – texts to be read by the passers-by of their own times just as much as, in lucky cases, by future generations. Such is the case, for example, of one Gaius Gargilius Haemon, a pedagogue and imperial freedman, who, despite his humble background, was able to commission, while still alive, a wonderful verse inscription in iambic senarii on a marble tablet from the City of Rome:

C(aius) Gargilius Haemon Proculi

Philagri divi Aug(usti) l(iberti) Agrippiani f(ilius)

v(ivus) paedagogus idem l(ibertus).

pius et sanctus

vixi quam diu potui sine lite

sine rixa sine controversia

sine aere alieno, amicis fidem

bonam praestiti, peculio

pauper animo divitissimus.

bene valeat is qui hoc titulum

perlegit meum.

Gaius Gargilius Haemon, son of Proculus Philagrius Agrippianus, pedagogue and freedman of the deified Augustus, while still in life. I lived in a pious and virtuous way as long as I could, without lawsuits, scuffles, and controversies, without debts. I trusted only my friends, I was poor concerning money, but very rich in spirit. May be well he who carefully reads this inscription of mine.

(CIL VI 8012 = CLE 134 = ILS 8436 = EDR127590. For an image click here)

Just like Caterina’s epitaph, this piece gives brief summary of the life of the deceased, Gargilius Haemon, who, as the text suggests, was able to live peacefully, dutifully and virtuously. The humble origin of the man is not concealed, but it is balanced, and ideally overcome, by the richness of spirit, as Peter Kruschwitz pointed out in an earlier piece. Despite his poverty, Gargilius Haemon managed to commission an epitaph, that in this man’s imagination meant cheating oblivion, especially when combined with an appeal to the careful and attentive reader. The phrase qui hoc titulum perlegit meum does not only reach out to Gargilius Haemon’s own contemporaries, but rather it is an appeal to humankind, to posterity, and that certainly includes ourselves. Thus, Gargilius Haemon’s case is, to an extent, almost the same as Caterina’s – and thus, for as long as we are able to read their last words, we will contribute to an everlasting attempt to rescue them from the darkness of oblivion.

Despite their undeniable difficulty of expressing themselves and of presenting their lives and accomplishments, there are many instances of the not-so-rich and not-so-powerful who managed to leave a trace of themselves to posterity thanks to the poetry they had inscribed on durable marble. Since the dawn of civilization, we can say, both the poor and the rich have tried to conquer time and its relentless passing. But, mankind has always been deeply aware of it, human time is all too powerful, and eventually, sooner or later, it scatters traditions, people, and potentates. Yet, aware of this truth, our own duty remains that of perlegere, that of reading carefully from beginning to end, the last words of those who preceded us, and to ask for peace for them, in this eternal fight, against time and dreaded nothingness – a fight that we, too, will lose eventually. And November, the month of the dead in many cultures, is perhaps the most appropriate time to keep alight the candles of memory.

Tempus edax rerum Castagna Cemetery (Genoa Sampierdarena). Photo: Mirko Tasso (November 2018)

A-e mae reixe