Epigram of the month: Vidi pyramidas

After a year of pandemic and deprivation, I think we all want a bit of freedom back. Yes, we used the crisis as an opportunity to be part of digital events all over the world without leaving our desks at home. Team MAPPOLA hosted a workshop on “Latin Poetry in the Greek East & Greek Poetry in the Latin West” that brought together specialists from different continents online who probably could not all have met offline. It was inspiring! And yet, after a year in a permanent state of emergency, I miss one thing in particular: travelling.

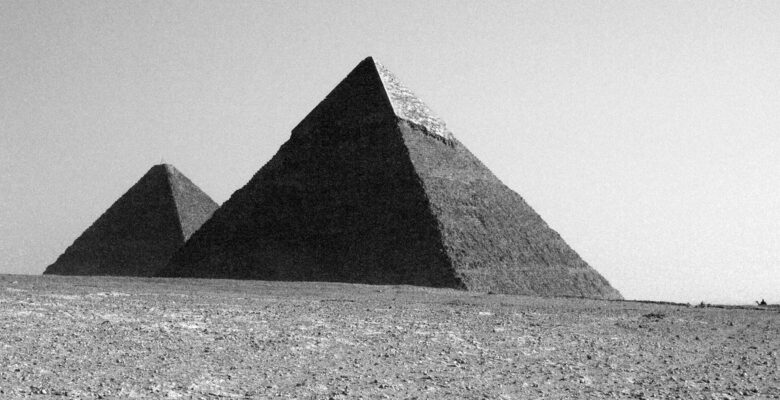

When Covid-19 reached Europe in spring 2020, I was working on an archaeological dig in Luxor, Egypt. At some point, news reached us that Austria was preparing for the lockdown. I took one of the last planes leaving Egypt the day before the Austrian lockdown. And I was lucky twice: from my seat I could see the pyramids in the distance. Two weeks later, I started my job at the MAPPOLA project in Vienna and immersed myself in the world of Latin epigrams. And there I read a line that has stuck with me to this day: Vidi pyramidas sine te dulcissime frater. (CLE 270 l. 1) Suddenly I asked myself: (When) will I be able to see the pyramids again?

More than a year later, I still can’t answer this question for sure. But I’ve had time to read a little more about the poem CLE 270 = CIL III 21 = CIL III 6625. It was once written on one of the two larger pyramids at Giza and its text is only preserved because the German pilgrim Wilhelm von Boldensele copied it in 1335 in the account of his travels through Egypt. (See Erhart Graefe’s article on the pyramid visit of Boldensele.) Alongside it, other inscriptions in different languages were carved into the smooth limestone surface by Greek and Roman travellers. Because this facing was later removed and used as building material for Cairo, all inscriptions are lost.

Wilhelm von Boldensele reproduced the text as follows (given in the revised reading by Bücheler):

Vidi pyramidas sine te, dulcissime frater,

et tibi quod potui, lacrimas hic maesta profudi

et nostri memorem luctus hanc sculpo querelam.

sic nomen Decemi Gentiani pyramide alta

pontificis comitisque tuis, Traiane, triumphis

lustra[que] sex intra censoris consulis exst[et.

I saw the pyramids without you, my dearest brother, and here I sadly shed tears for you, which is all I could do. And I inscribe this lament in memory of our grief. May thus be clearly visible on the high pyramid the name of Decimus Gentianus, who was a pontifex and companion to your triumphs, Trajan, and both censor and consul before his thirtieth year of age.

(Translation: Emily A. Hemelrijk)

The six hexameters honour one Decimus Terentius Gentianus (RE V A,1 Terentius 48, cols 656-662; PIR T 56) whose career – and gentilicium, which was omitted here due to metrical reasons – is known from CIL III 1463. He was suffect consul under Emperor Traian in AD 116 and censitor (tax official) of Macedonia under Emperor Hadrian in AD 120. He died within six lustra, i.e. before he turned 30, having thus attained his ranks at a young age. The poem also tells us that Terentius was given the great honour of taking part in Traian’s triumphs. This most likely refers to Traian’s posthumous triumph over the Parthians in 117, for Terentius was too young for participating in the triumph over the Dacians ten years earlier.

It is unclear whether the inscription is complete, as it is not directly expressed who commissioned the poem. Wilhelm von Boldensele may (or may not) have overlooked an addition engraved below the metric part, revealing the name of the relative.

But let’s take a closer look at the wording:

In line 1, the deceased is addressed as a brother. In line 2, the adjective maesta reveals that the speaker is a woman, because it is written in the feminine form. That means that the one who is in sorrow is his sister. Her name must have been Terentia after the gentile name of her family, which is attested for her brother.

Now, think about it: Terentia, coming from a senatorial family, toured Egypt and left a funerary poem commemorating her brother on one of the largest funerary monuments in the ancient world. By chance, or perhaps because it was prominently placed, it is the only Latin inscription from this monument that has survived.

And even after the stone is long gone, people still write articles and blog posts and Twitter threads about the two siblings and relate to the emotions expressed in the poem.

I am curious what Terentia saw when she looked at the pyramids. The smooth surface must have been full of text in different languages, much like the Colossi of Memnon – where other Greek and Latin poems can be found – and the walls in the tombs in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, which still bear witness to ancient tourism.

Colossi of Memnon, Luxor | Graffiti in the Valley of the Kings, Luxor. Photos: T. Hobel

Could Terentia have read other poems besides her own? Could she have used them as inspiration for her own text? Did she follow what others before her wrote on the pyramid(s), or did she do something different?

We’ll never know for sure. But by examining poetic spaces and their communicative settings in our project, we hope to better understand poetic interaction in inscriptions.

Let’s hope that travel will soon be possible again without any problems, so that we can explore these spaces. I would like to start by visiting the Colossi of Memnon again and taking better photos this time. (“I’ll do that next week!” didn’t work for me in spring 2020.) I might even tweet about it or write a blog post.