Housekeeping, or: Vienna’s Oldest Poetry

MAPPOLA is an ambitious project – there are literally thousands of verse inscriptions from across the Roman world, written in Latin and in Greek (and probably in a number of additional languages as well).

But since we are based in Vienna, it was important to us to start with what we have here – around us. So far, among many other things, we had been able –––

- to compile a list of pieces from the nearby Roman settlement of Carnuntum (available with a German translation here),

- to write a short article on a Roman clay tile from Vienna with a metrical text on it (to be published in the next issue of Tyche),

- to inspect an inscription from nearby Aequinoctium – St. Margarethen am Moos, and

- to inspect a little sheet of gold leaf with a pierced inscription on it, kept in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, reported as of Viennese origin.

Dr González Berdús investigating a gold lamella in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Today, we were fortunate enough to be given access to the storage facilities of the Wien Museum, which houses the only monumental verse inscription that has come to light from Roman Vienna – Vindobona – thus far.

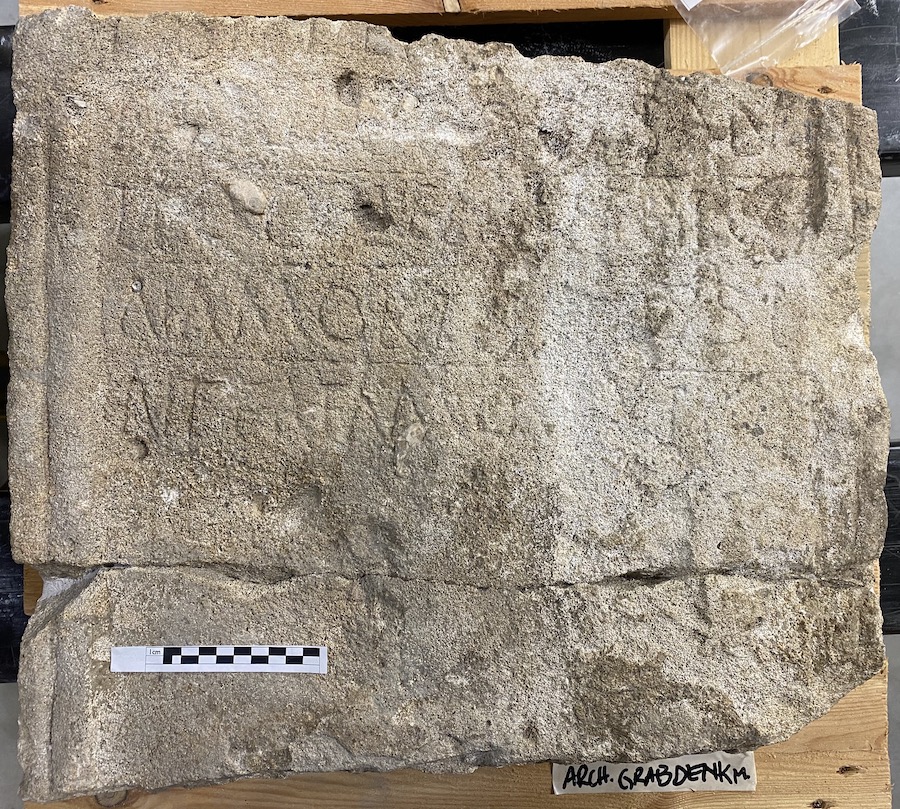

Prof. Kruschwitz studying a Viennese tombstone in the Wien Museum storage facilities.

So, what have we got for Vienna (and its immediate vicinity)?

Nothing much in terms of numbers, sadly.

But we are glad to share the texts (and translations) of what we have, including images with kind permission of the relevant institutions (all image rights remain with the right holders).

A Christian tombstone from Roman Vienna

Text

– – – – – –

nisinie +++[- – -]+[- – -]

Marcio coni(ugi) san-

te. o(biit) (vel Θ?) oṛ(a) V. n[o]n dig-

na mori s[i] pọssi-

nt fata mou[e]ṛi. (hedera)

(AE 1956.9)

Translation

. . . for [—]nisinia . . .: . . . Marcio had this made for his saintly wife. She died in the fifth hour [i. e. around 9 a.m.].

She had not deserved to die, if (only) the Fates might be moved.

Notes

The item, discovered in secondary use in Vienna’s legionary camp, has been dated to the fourth century A. D., and it is commonly regarded as Christian. Both assumptions may be false: the stone may well belong to an earlier date than that, and the Christian connection rests on the indication of the hour of death alone (which is tenuous).

The bit that reads n[o]n dig|na mori s[i] possi|nt fata mou[e]ri is essentially a dactylic hexameter (with an irregularity at the beginning).

Earlier scholarship presents the piece with a number of false readings, including the initial name (which has variously been interpreted as Sabina or Sabinia. We are confident, however, that this is incorrect and that the above text is what the stone says.

The name of the deceased may have been [Bo]|nisinia, or this may have been a variant of the hitherto unexplained name IAIIONISINVS of the (equally Pannonian) stone for Bononius Vitalis.

Excellent images are available from our friends of the Lupa project.

A roof tile from Roman Vienna

Text

Venturam

terris

uiḍ[- – -]

– – – – – –

(AE 1992.1452 = AE 2015.1102 )

Translation

Behold the (sc. tile) that is about to fall to the ground . . .

Notes

Just as the previous stone, this item – fragments of a clay tile, inscribed ante cocturam, i. e. before the tile was baked – was discovered in the context of Vienna’s legionary camp.

It is reasonable to assume that this was a self-referential inscription in which the writer was reflecting, possibly in a humorous manner, on the possibility that this tile was eventually going to fall to the ground: this is a common subject matter (including in references to individuals being killed by falling-down objects from Roman roofs): we will expand on this in a forthcoming article.

The inscription, undated, preserves a dactylic rhythm (which may or may not have amounted to a full hexameter or pentameter at some point).

. . . and that is it for Vienna! The piece we looked at in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, as far as we know, is from Italy (more on that in an article that we are currently drafting).

But, no need to be sad! Let’s throw in the item from Aequinoctium – called equinox maybe because it was halfway between Vindobona and Carnuntum – now kept in the church of St. Margarethen am Moos!

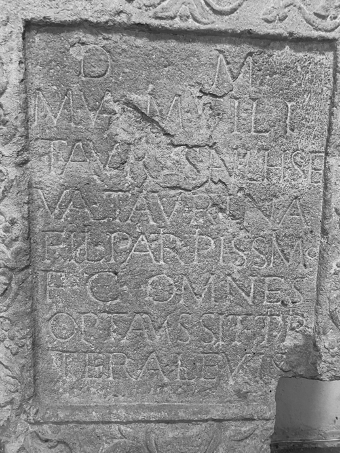

A tombstone from Aequinoctium

Text

D(is) M(anibus)

M(arcus) Va[l](erius) M(arci) fili(us)

Taurus an(norum) L h(ic) s(itus) e(st).

Val(eria) Taurina

fili(a) patri piissimo

f(aciendum) c(urauit). Omnes

optamus sit tibi

tera leuis.

(CIL III 4533 = 11294)

Translation

To the Spirits of the Departed.

Marcus Valerius Taurus, son of Marcus, is buried here, aged 50.

Valeria Taurina took care of the execution (sc. of this monument) for her most dutiful father.

We all wish: may earth rest lightly on you.

Notes

The stone was once inserted into the church’s outer wall, and it has since been moved to the side nave.

Datable to the second century A. D., this piece, richly decorated with sculptures, is particularly striking with its central representation of a rampant lion over a human body:

Lions are common in funerary art, yet this particular type is rather unique. Perhaps the lion is a representation of a guardian, watching over the deceased?

The inscription itself, beautifully executed with a number of remarkable ligatures, employs a noticeable gap to set apart its final two and a half lines from the remainder of the text:

These final few lines that read Omnes | optamus sit tibi | tera leuis (‘we all wish: may earth rest lightly on you’) reworks the common formula s. t. t. l. into a single pentameter, employing a formula in a regional variant that is specific to the Danubian provinces (sometimes also given in abbreviation, o. s. t. t. l.), optamus sit tibi terra leuis, ‘we wish: may earth rest lightly on you’.

Further material is available from our friends of the Lupa project.

And that’s all for now. Of course, we hope that over the next few years, more items will come to light. But it is a start, and with that we have done our housekeeping in the immediate vicinity – grateful for all the wonderful support we have received from the museums.

Onwards!