Behind the scenes: Mors immatura at the Mainzer Steinhalle

by Victoria González Berdús and Yolanda López Sánchez (Universidad de Sevilla, FPU predoctoral researcher funded by the Ministerio de Universidades, Gobierno de España, within the CLEO project), our academic visitor at Universität Wien from March to June 2022.

Over a year ago, on occasion of International Museum Day, we dedicated a blog post to the Mainzer Steinhalle, a section of the Landesmuseum Mainz (Germany) that holds one of the most important epigraphic collections in Europe. Its original size had been reduced to make space, temporarily, for the Rheinland-Pfalz Parliament, and there were some conversations about potentially using these new installations as a Demokratie-Labor, once it was no longer used as home to the Parliament – a plan that prompted an international reaction asking for the Steinhalle to remain as it originally was.

We declared our love for the Steinhalle by choosing three of the many Latin verse inscriptions that are preserved in its collection and telling the world what makes them special and valuable. Until recently, however, not least due to the pandemic, we had never had the chance of actually visiting the Museum and getting to know the space and the people who work there every day with such incredible material.

Yolanda López Sánchez, our academic visitor here in Vienna, is currently working towards the textual edition and a full-scale study of the carmina Latina epigraphica from Germania Superior for her doctoral thesis, and for that, naturally, she was all set to see, in person, as many verse inscriptions from Roman Mogontiacum as possible. Naturally, we had to jump on the opportunity of travelling along and studying some of the pieces.

The Mainzer Steinhalle is currently open to all visitors of the Landesmuseum Mainz, and it offers a curated selection of Latin inscriptions, with a very strong presence of pieces that are either dedicated, or make reference, to the military presence in the city.

Besides this, there are currently four verse inscriptions on display.

In order to commemorate our visit, we will highlight two of them, which stand on their own because of their originality and the stories they tell. At the same time, they are an excellent representation of the poetic production of Mogontiacum.

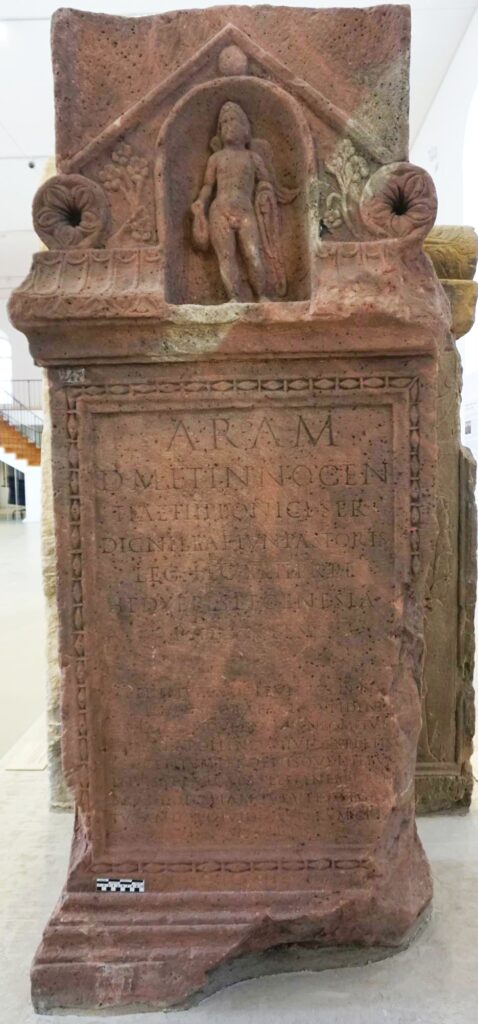

The first inscription is a beautiful monumental altar dated between 157-159 AD:

Aram

d(is) m(anibus) et innocen-

tiae Hipponici ser(vi)

Dignillae Iun(i) Pastoris

5 leg(ati) leg(ionis) XXII Pr(imigeniae) P(iae) F(idelis)

Hedyepes et Genesia

parentes.

ut primum adolevit pollens

viribus decora facie Cupidinis

10 os habitumque gerens nec metuam

dicere Apollineus huic expletis

ter centum ter denisque diebus

invisae Parcae sollemnem cele-

brare diem iamque ut esset gra-

15 tus amicis invidia superum cess[a]-

vit amari.

(CLE 1590 = CIL XIII, 6808)

Altar for the Spirits of the Departed and the innocence of Hipponicus, slave of Dignilla (wife of) Junius Pastor, legate of the legio XXII Primigenia Pia Fidelis, (erected by) Hediepes and Genesia, his parents.

As soon as he matured with great strength and with a beautiful face, with the aspect and appearance of Cupid, and, I will not be afraid to say it, apollonian, having completed three hundred and thirty days, the Fates became envious of him celebrating his solemn day and, being already so loved by his friends, because of the envy of the gods he ceased to be loved.

Hipponicus, the recipient of this poem, is compared to Cupid and Apollo because of his beauty and appearance (Cupidinis / os habitumque gerens nec metuam / dicere Apollineus, ll. 9-11).

This idea is also reflected in the iconography of the monument: in the relief inside the superior niche, there is a nude male figure with muscles, curly hair and wings. He holds in the right hand a mantle, maybe the toga virilis, which goes around his back and rests on the left arm, whose hand holds a cane.

The physical qualities and the attributes remind us too of the representation of Cupid or Apollo. It is undeniable, however, that the figure looks more like a child (and it has thus been included in J. Mander’s Portraits of Children on Roman Funerary Monuments, 2013, no. 454) than like an adult. This and the slightly obscure mention of the passing of almost a year and a birthday that the deceased could not celebrate (huic expletis / ter centum ter denisque diebus / invisae Parcae sollemnem cele/brare diem, ll. 11-14) have led to believe that Hipponicus was a little baby at the time of death.

Could this mean that the child was considered to be divinised? This would be the only case found so far among the Latin verse inscriptions from Mainz, but the imitatio deorum or consecratio in formam deorum is a practice well attested (ibid., 55-64).

Divinised or not, in the course of time there has been some controversy around the age of the deceased. As mentioned, one could understand from ll. 11-12 that the child was three hundred and thirty days old. However, this does not seem to match with the physical description at the start of the carmen, where it says ut primum adolevit pollens viribus decora facie, a verse clearly inspired by Sallust’s Bellum Iugurtinum: Qui ubi primum adolevit, pollens viribus, decora facie, […]. Here Sallust refers to the moment Jugurtha became an adolescens, for which he uses the formal verb adolevit.

The mention of Hipponicus having friends (gratus amicis, ll. 14-15) is also somewhat impressive for a one year old, especially followed by the idea that he was so very much loved and appreciated by them that the gods became jealous, which prompted his death.

Taking all of this into account (the comparison with Cupid and Apollo, his representation in the niche, the literary parallel and the mention of his friends), we must ask ourselves: was Hipponicus really almost one year old when he passed away? It seems logical to be at least a bit sceptic.

The other option, on the other hand, is much simpler: the mention of the three hundred and thirty days is there only to emphasise how close Hipponicus was to reaching his next birthday. Thus, the sollemnis dies would only refer to his last birthday and not to the first one. At the time of his death, that may have occurred as he was about to turn fifteen, he must have been a beloved and attractive young man full of potential. For his parents, the only way to rationalise his mors immatura – while indirectly praising Hipponicus – is blaming it on a superior power that also suffers from human flaws, such as spite.

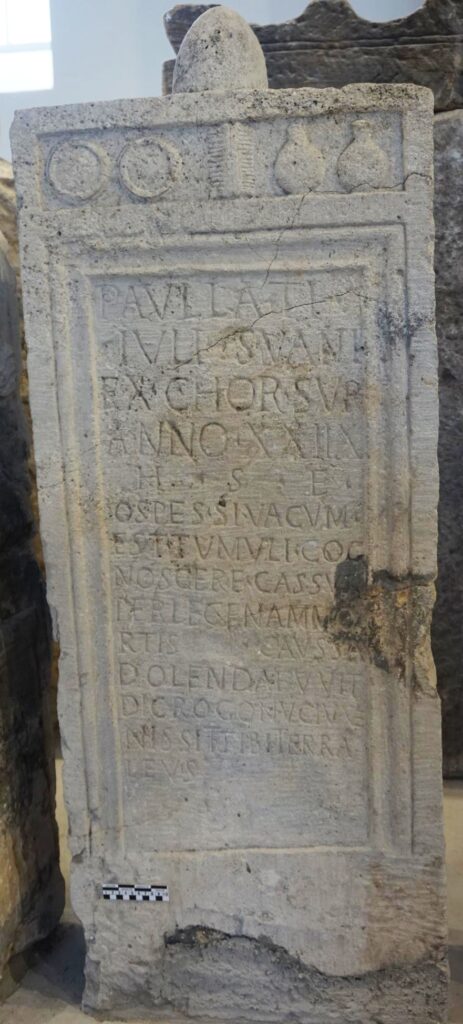

The next piece is a funerary stele dated during the first half of the first century AD. As with the previous inscription, after reading the text we are left with a few questions.

Paulla Ti(beri)

Iuli Selvani

ex c(o)hor(te) Sur(orum)

anno(rum) XXIIX

5 h(ic) s(ita) e(st).

(h)ospes si vacu(u)m

est tumuli cog-

noscere cassus

perlege nam mo-

10 rtis (vac.) caussa

dolenda fuuit.

dic rogo nu(n)c iuve-

nis sit tibi terra

levis.

(Zarker 113)

Paula (daughter/wife) of Tiberius Iulius Selvanus from the Syrian cohors, aged 28, lies here. Traveller, if it is possible to know the tragedy of this tumulus, continue reading, since the cause of the death was very unfortunate. Say now, I beg you: “Young woman, may the earth rest lightly on you”.

The epitaph is dedicated to Paulla, who was twenty-eight years old and is characterised as a young woman throughout the carmen but also by the reliefs on the upper part, with a mirror, a hairbrush and an unguentaria. Her name in the praescriptum is followed by the tria nomina Iulius Tiberius Selvanus in genitive, which has two possible interpretations: Paulla is either the daughter or the wife of Tiberius. Given that we do not have any more information regarding Paulla, their family connection remains a mystery. We do have, however, more data about Tiberius in the praescriptum: he belonged to the cohors Surorum at the time of Paulla’s death.

Given that there is no other epigraphic evidence of the presence of this cohors Surorum in Mogontiacum, we have to turn to literature. In particular, Tacitus (Annales IV, 73) mentions a Phrygian revolt in Germania in the year 28 AD. In order to put it down, Rome sent legionary detachments and auxiliary troops. Among these we find the cohors I Ituraeorum, composed by Syrian soldiers and whose presence in Mainz is documented both in epigraphic and literary sources during the first half of the first century AD. The cohors I Ituraeorum is attested in many places with different names and stamps (see O. Ţentea, Cohors I Ituraeorum sagittariorum equitata milliaria, in L. Rusc et al. (eds.) Orbus Antiquus. Studia in honorem Ioannis Pisonis, 2004, 805-814), and one of them is c(o)h(or)s S(urorum), as it appears in this inscription. Thus, we can identify this cohors and its presence in Mogontiacum during the first century A. D. Also, the Syrian origin could explain the iconographic characteristics of the piece, so far unique in the Mainz area.

Another mystery related to this inscription is the mortis causa of the deceased. As we read, we get the impression that we are about to find out: si vacu(u)m / est tumuli cog/noscere cassus / perlege (ll. 6-9). We carry on, but we only find another explanation introduced by nam, which does not shed a light on the cause of death and only describes it as dolenda, thus emphasising the pain caused by it. In addition, there is a clear vacat between mortis and caussa (ll. 9-10). During our autopsy we were able to observe that the surface of the stone at this point is clearly worn out, as if some word had been deleted.

What could it be?

Perhaps the poem was copied from another epitaph and the cause of death was different, so it was later erased. Or maybe it was a simple mistake by the stonecutter, who deleted a word and then decided to keep inscribing the text where the surface of the stone was in better condition. The metrics of the carmen could favour this theory: adding a word between mortis and caussa would alter the scheme of the pentameter (perlege, nam mortis caussa dolenda fuuit). This, however, would not be a rare occurrence among Latin verse inscriptions: often personal information is added to very common and wide-spread sequences.

In any case, the sequence mortis caussa dolenda fuuit allows us to think that special circumstances were involved in Paulla’s death. Thus, could this be a veiled reference to a mors singularis? At any rate, this could be a poetic way of characterising Paulla’s death as a mors immatura.

Luckily, the future looks bright for the Mainzer Steinhalle: last December it was announced that the City of Mainz no longer had the intention of using the new installations as a democracy forum. We look forward to future visits to Mainz and are excited to see what the future holds for one of our favourite epigraphic collections.

We would like to close this post by expressing our deep gratitude to Frau Dr. Ellen Riemer, responsible for the Archaeology section of the museum, who helped us every step of the way, and also to all the Museum staff, who kindly put up with our intense autopsy-ing and squeeze-ing.