Nobody puts the Mainzer Steinhalle in a corner

by Chiara Cenati and Victoria González Berdús

On International Museum Day, we would like to tell you a story that deeply touched us: the story of the Hall of Roman Stone Monuments at Mainz (Mainzer Steinhalle). This story doesn’t take place in the past, once upon a time so to speak, but it is happening right now, in front of our eyes – and its ending is still to be written.

The story takes place in in Mainz, Germany, in the heart of Europe.

In Mainz, there is a famous regional museum, and in this museum, there is a room, the Steinhalle, that is meant to host, among other Roman remains, the numerous inscriptions of ancient Mogontiacum.

Over the last five years the Steinhalle has been gradually emptied so that the Parliament of Rheinland-Palatinate could meet there while their plenary hall was being refurbished. Now the renovation works are finished, and the Steinhalle could resume serving its original purpose.

So what is the problem then?

Well, it turns out that the president of the parliament at Mainz thought it would be a good idea to repurpose this venue in order to set up a “democracy forum” there instead.

Never, not even in our worst nightmares, we imagined that a democracy project might have threatened and replaced a museum, this museum, a place of history, and especially a place dedicated to the history of the common people: the δῆμος – the people who literally put the demo– into democracy.

Let us put things into perspective.

The epigraphic collection in Mainz is one of the most important ones of its kind in Europe. The building that houses the collection dates back to the 18th century, and it was transformed into the Steinhalle in 1964, almost 60 years ago. Initiatlly, it wasn’t a proper exhibition: it looked more like a storage room, but it was already a vast improvement, given that, until then, most of these inscriptions had been kept outdoors. Before its 1964 transformation, the venue had served as a riding arena and also as a theatre.

The inscriptions of the Steinhalle are direct testimonies of the first inhabitants of Mogontiacum, a very intercultural and international centre. The population of Mogontiacum would have resembled that of many European capitals today, with people coming from all over the Roman Empire. Situated right at the edge of the Roman territory, the original double legionary camp that was to become present-day Mainz appears to have been built around 13/12 B.C. to secure and defend the empire’s wet border that was the river Rhine. From these beginnings, a prosperous city developed during the following centuries.

Already well before that continuous urban and economic development, poetry – yes, it’s our favourite topic! – had emerged: the oldest verse inscriptions that have been preserved date to the first quarter of the 1st century A.D. – these pieces thus include some of the oldest pieces of locally produced and preserved poetry of Germany, the self-proclaimed Land der Dichter und Denker (‘the country of poets and thinkers’).

Putting this invaluable (not an hyperbole!) material back into storage would mean denying public access to immense cultural heritage, denying access to a place where new generations can get in contact with, and understand, the past, denying access to a place where all visitors can learn about the history of the city they live in or that they visit – and especially where they can learn about the individuals who lived and died there before them.

For us as epigraphists, this move means the loss of one of the most meaningful collections: a gateway to antiquity is in danger of being closed.

But why are inscriptions the first pieces to end up in a depot if the space of an exhibition is reduced?

Why are epigraphic collections deemed unimportant even by well educated people (as we trust the president of the Parliament of Rheinland-Palatinate is)?

The value of these objects is not (or not just) visual, but in the double historical significance that they carry in them: they are both artefacts and texts.

As far as verse inscriptions are concerned, their artistic value is even higher. This may be less apparent than in it is in the case of statues or paintings. But these texts are works of art, crafted from material that unites us all, language, words – texts that once would have been read out aloud by their readers, and heard by the passers-by.

And the first inhabitants of Mogontiacum did not just leave us with their impressively beautiful inscribed monuments – monuments whose artistic value survived to the present day. These monuments also often feature delicate plant motifs and / or some small reference to the deceased.

Sadly, their tremendous aesthetic and cultural value has not (yet) been sufficient to grant these inscriptions a dignified, unchallenged place on public display.

So let us do what the government of Rhineland-Palatinate would appear to be unable (or unwilling) to do. Let us show you what you will be missing in the future, if these plans go through.

Let us give a voice to some of the original inhabitants of Mogontiacum: a legionary soldier, a cattle-breeder, and the parents of a little girl. All of them worthy inhabitants of the Mainzer Steinhalle. (And if as a result you would like to learn more about the carmina from Mogontiacum, great!, they are currently the topic of a broader project on the poetry of Roman border cities, carried out by us of Team MAPPOLA here at the University of Vienna).

Gaius Iulius Niger, the legionary soldier (1st quarter 1st cent. A.D.)

C(aius) Iulius C(ai) f(ilius) Vol(tinia)

Carc(asone) Niger, mi–

les leg(ionis) II, annor(um)

XXXXV, aer(orum) XVII

h(ic) s(itus) e(st).

hospes ades paucis et perlege uer-

sibus acta. aeternum patriae hic

erit, ipsa domus hic erit, inclusus tumu-

lo hic Iulius ipse, hic{s} cinis ex caro cor-

pore factus erit. cum mea iucunde

aetas florebat, ab annis aduenit fatis

terminus ipse meis. ultimus ipse fuit

XXXXV annus, cum mihi fatalis ue-

nit acerba dies. hic ego nunc cogor

Stygias transire paludes, sedibus aeter-

nis me mea fata tenent. me memini Gal-

lia natum caroq(ue) pare[nt]e et miles collo

fortiter arm[a t]uli. Gallia crudelis tri-

buit mihi [fu]nu[s et ignem et] cu[l]tos artus ter-

ra cinisqu(e) p[remunt? —]to gnatus

miles leg(ionis) II P[—]AT heri(s) (!)

eius est.

CIL XIII 7234 = CLE 1005 = CSIR-D-02-05, 79 = http://lupa.at/15914

Gaius Iulius Niger, son of Gaius, of the tribus Voltinia from Carcaso, soldier of the legio II, aged 45, with 17 years of service, lies here.

Stranger, be still and read what is said in a few lines. Eternally here, in his homeland, he will be here in his own dwelling, he will be here enclosed in the grave, here, Iulius himself, here ashes will be made from the beloved body. When my life was blooming nicely, the end point came for my years. My 45th year was the last one, when the fatal day arrived for me. Now I am forced to cross the Stygian swamps, my fate holds me in the eternal dwelling. I remember that I was born in Gallia and of my beloved father and that, as a soldier, I bravely carried the weapons around on my neck. Cruel Gallia has granted me death [and fire,] and earth and ashes rest on my sheltered limbs. [the remainder text is too fragmentary]

(Transl. VGB)

We know what you are thinking: well… this is not… that pretty? After reading the beginning of the poem, written in elegiac couplets, it is likely that your first thought was ‘I get it, Gaius Iulius Niger WAS buried there’.

Let’s take a step back.

Thanks to a careful ordinatio, the personal information is written in bigger characters.

After that, we are forced to come close, and that’s where it gets personal.

He came from far away, but now he lies here, here is his homeland, here he lived, here is he buried, here are his ashes.

Why would someone want to emphasise so deeply their place of burial and only give a small hint about his life?

The answer is easy: he is not an inhabitant of Mogontiacum by birth, but by choice.

The legio II Augusta remained in Mainz approximately between 9-17 B.C. This was enough to make Iulius feel at home. Gallia, his place of birth, did not represent a happy memory for him: it was death and fire. His childhood in Gallia, his father, and the first years as a soldier were just vague pieces of a misty past.

Mogontiacum was his present, the place he belonged to.

His funerary stele has all the rights to occupy a place in the Steinhalle. More so when it is the only poem produced by a soldier of the legio II Augusta.

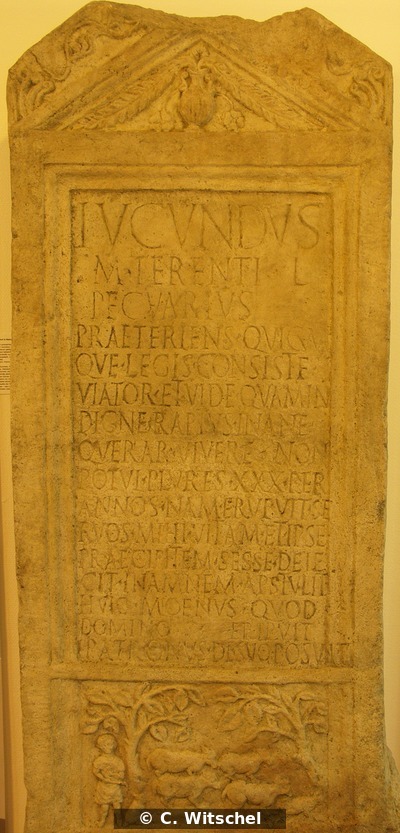

Marcus Terentius Iucundus the cattle-breeder (1st half of the 1st cent. A.D.)

Iucundus,

M(arci) Terenti l(ibertus),

pecuarius.

praeteriens quicum-

que legis consiste

uiator et uide quam in-

digne raptus inane

querar. uiuere non

potui plures XXX per

annos, nam erupuit (!) se-

ruos (!) mihi vitam et ipse

praecipitem ses{s}e deie-

cit in amnem. apstulit

huic Moenus quod

domino eripuit.

patronus de suo posuit.

CIL XIII 7070 = CLE 1007 = CSIR-D-02-06, 52 = HD056389 = http://lupa.at/16500

Iucundus, freedman of Marcus Terentius, cattle-breeder. Whoever reads this on their way: stop, traveller, and watch as I complain in vain, undeservedly snatched (from life). I could not live more than 30 years, for a slave took my life away from me, and then he threw himself headlong into the stream. The Main snatched from him what he had taken away from his master (i. e., his life). His patron had (this monument) erected with his own money.

(Transl. VGB)

This short poem, again in elegiac couplets, contains in a few lines the chronicle of the violent death of Iucundus (and a nice little example of karma? We shall see).

As before, the personal information is written in bigger characters that very likely could be read just as someone walked past the monument.

After that, the instructions are clear: consiste, we are talking business now, you should stop and pay attention.

Iucundus was born as a slave, but he was still young when his master, who perhaps loved him as his own child, freed him and gave him his own name, as parents do. Now he had three names, the tria nomina: something to be proud of. He was in his twenties, a free man with a job (2000 years later: it is not so easy…). One day, as his sheep were grazing as always along the river Main, he was surprised by his own slave, who killed him (not quite a iucundus finis, right? right??) and then jumped into the river, probably trying to escape, but finally dying himself (karma!).

Of the killer we just know he was a slave. His name is not as important as the fact that he was different (lower social status, maybe a different colour of the skin, another religion: this is already half of his guilt).

So, what was really the connection between the victim and his murderer? Was the slave jealous of him? Or was Iucundus now an evil master himself, forgetful of his own origins? We don’t know it. What was the motivation of the murder? Also difficult to say. Iucundus’ master, Marcus Terentius, didn’t forgive the homicide. Instead, he prepared an eternal memory for Iucundus, dedicating a poem with a portrait of him in a bucolic everyday scene, which at the same time provides the evidence of an ancient crime. And by the way, removing the evidence from the crime scene is a crime itself.

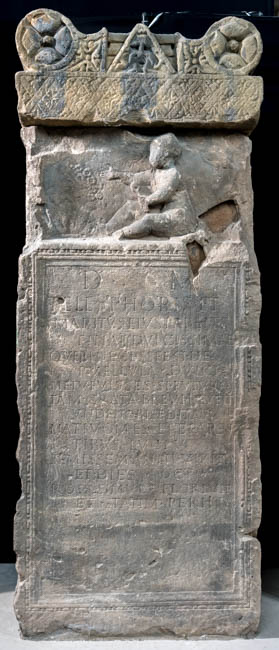

A very sweet little girl, whose name we don’t know (2nd-3rd cent. A.D.)

D(is) M(anibus).

Telesphoris et

maritus eius parentes

filiae dulcissimae.

queri necesse est de

puellula dulci.

ne tu fuisses, si futura

tam grata breui reuerti

unde nobis edita

natiuom (!) esset et paren-

tibus luctu.

semissem anni uixit

et dies octo.

rosa simul floriuit

et statim periit.

The funerary stele of the little baby girl. Source: http://lupa.at/16695. © Mainz – Landesmuseum, Foto: Ortolf Harl 2016 November

To the Spirits of the Departed. Telesphoris and her husband, parents to their sweetest daughter.

It is necessary to grieve for this sweet little girl.

You should not have existed, if the one who was destined to be so loved was born to shortly return whence (!) you were sent to us and thus, be a cause of mourning to your parents. She lived half a year and eight days. At the same time (!) as the rose she blossomed and suddenly perished.

(Transl. VGB)

This text is written in iambic rhythm. As you may be able to tell, the Latin used here is not especially smooth. We understand what it means, but the words and the syntax are not quite right: it doesn’t matter.

The poem would be moving enough without the portrait of the baby girl on the top. Seeing her, caught in an everyday scene, like in a photo taken by her mother, while she was playing on the floor with what looks like a rattle and – new achievement! – keeping her back straight, just makes you want to cry.

If this funerary monument had a screen on it, with a short movie in a modern language instead, nobody would dare to move it from where it is.

This inscription expresses the most devastating pain of a mother and of a father, both parents of a little girl who was growing up day by day before their eyes and was then suddenly snatched away from them. Instead of feeling the incredible pain caused by this loss, they would have preferred to have never experienced the joy of being parents. As a beautiful rose that suddenly withers and dies (a very common comparison in Greek and Latin epigraphy), the death of their little one seems to have been unexpected.

Oddly enough, this was not the first inscription for Telesphoris’ daughter.

Probably in a hurry after her death, they had dedicated another monument to her, this one with no poem and poorer decoration, which they kept on the grave next to the new one with verses. Ancient people were more used to facing death than us, especially of new born kids, though this didn’t prevent them from feeling unnatural and immense grief and wanting to properly honour the little life that had been lost.

Verse inscriptions are both ancient and yet they feel eminently modern.

Verse inscriptions tell the extraordinary stories of ordinary people.

The voices of Niger, Iucundus and Telesphoris’ little daughter are not filtered by centuries of literary tradition. They are directly addressing us, and they must be allowed to continue to do so in their hall, in the museum!

If you also feel as saddened and as outraged as we do, please help us to write a happy ending for this story.

Sign the petition, leave a comment, share the voices of the Roman-era inhabitants of Mogontiacum.