Guest blog: Greek epigram in the Roman west, by Gideon Nisbet

We are delighted to share the script of the brilliant presentation that Gideon Nisbet (University of Birmingham) gave on occasion of our first MAPPOLA workshop.

Gideon has now published his talk on his fantastic Lector Studiosus blog: we are very grateful to have his permission to re-blog it here. Make sure to visit Gideon’s blog regularly – there is so much to discover! And his handout for the talk is available here.

INTRO

Greetings and thanks

It’s my pleasure to have this opportunity to introduce my new translation from the Greek Anthology for the World’s Classics,

By way of a small sample of Greek epigrams in the Roman West,

Including some that enjoy complicating that situation.

The book is available now, and I am blogging additional translations (Google me and ‘epigram’ and you’ll find them easily enough).

In all, my World’s Classics translation includes more than 600 poems,

Which is the biggest new version into English in a very long time,

And sounds like a lot, but is less than a sixth of what the Anthology contains.

What I’ve given you on the handout is a small sample for, I hope, your reading pleasure.

Its arrangement follows that of the source text,

But the story I’m spinning around them this afternoon is broadly chronological, so we’ll be hopping back and forth,

and I won’t discuss every poem in detail.

I’ll begin by briefly introducing my source:

The Greek Anthology that we read today, runs to sixteen books and contains about four thousand epigrams.

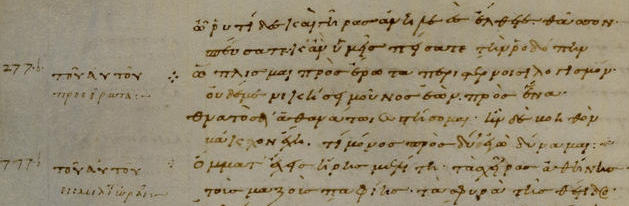

It is more or less the text of the Palatine Anthology, a tenth-century manuscript that in turn was more or less the Anthology that Constantine Cephalas had compiled not long before. Cephalas had gathered whatever he could from his classical and late antique predecessors, notably Meleager, Philip, and Agathias.

As a collection of epigrams, the Greek Anthology hits its stride with the erotic poems of bk.5.

It is front-loaded with oddities, inc. a collection of Christian epigrams; the Prefaces of Cephalas’s predecessors, from Meleager onwards;

and the strange little inscriptional collection that is the Cyzicene Epigrams — a pagan Stations of the Cross from a lost temple to an Attalid queen, and made up of scenes from Greek myth that illustrate the love of sons for their mothers. Though it’s notionally an artefact of the second century BC, it climaxes with the story of Romulus and Remus. This is the first item on your handout, but Book 3 is so weird and mysterious I’ll say no more.

EPIGRAMS OF MAGNA GRAECIA

Instead I’ll begin my tour on safer ground, by touching on Magna Graecia, which in Hellenistic times was as rich in epigrammatists as it had formerly been in lyric poets. Theocritus and Nossis, for instance, are significant presences in the Anthology. But they are poets, not of the Roman, but of the Greek West, with Rome still over the horizon.

Leonidas’s situation is probably different and I’ve given you one of his poems, from the dedicatory sixth book of the Anthology.

His home town of Tarentum, in Italy’s instep, was a rich Spartan foundation, and this poem celebrates a southern Italian victory for which the Tarentines erected a trophy at Pylos, in Sparta’s back yard. The metropolis helped out against the Oscan-speaking locals more than once in the mid- to late fourth century BC, so this feels plausible as a real inscription.

But modern scholarship places Leonidas’ floruit around 270, by which point the Romans had won the Pyrrhic War and pulled Tarentum’s walls down, so I suspect we are seeing an exercise in nostalgic avoidance of present realities.

PHILODEMUS, CRINAGORAS, ANTIPATER OF THESSALONICA

Later Hellenistic poets engage directly with Rome because it was a rich source of patronage. Their poems often accompany thoughtful little gifts that tastefully advertise the authors’ own modest means, as well as their warm friendships with wealthy and powerful individuals: a toothpick, for instance, or a nice warm hat. In a poem from Book 5, included on your handout, we see Philodemus of Gadara getting it on with a hot Italian girl. Cicero’s speech In Pisonem scolded Philodemus’s patron for picking up louche habits from his famous Epicurean houseguest, but Cicero himself was the proud sponsor of another Anthology poet, Archias.

In the next generation, Antipater and Crinagoras were kept busy celebrating Augustan family occasions. Antipater is represented on your handout by an epitaph for a Greek freedwoman, from the funerary Book 7; Crinagoras, by two poems from Book 9, including a very unlikely story about a parrot. The ninth book is ‘epideictic’, meaning displays of rhetorical skill. Since authors love showing off, it’s one of the Anthology’s biggest books. We have a secure context for Crinagoras’ other poem here, 9.516. He had passed through the Alps with Augustus on the way to Spain in 26/5 BC, and Gow and Page had fun wondering which animal’s fat it was that did the trick.

Palladas’s poem from the same book, 9.502, feels like it ought to belong to this early period — indeed I wonder if it can really be by him. This kind of cheeky banter with a patron would be more in Philodemus’ line, and by the fourth century AD even the most stubborn Hellene ought to have known what conditum was. (Plus, the poem is fun and Palladas is professionally miserable.)

NERONIAN POETS

Imperial patronage continued under the later Julio-Claudians. The Anthology’s other Leonidas, from Alexandria, specialised in isopsephic poems in which the letter-values of the first couplet — alpha as one, beta as two, and so on — added up to the exact same total as those of the second; and in the case of 6.329, of the third couplet as well. Or so he claims; his perverse party-trick has been a nightmare for modern scholars trying to emend the text so that the sums work.

Lucillius joined Leonidas in courting Nero’s patronage; he is famous for his scoptic or satirical epigrams, contained in the Anthology’s eleventh book, of which I give you two examples. I’m tempted to have ‘Marcus’ be Marcus Valerius Martialis, the poet Martial, who we know was heavily influenced by Lucillius. It’s a stretch — Martial began his major epigrammatic project of twelve numbered books in the 80s. But he was in Rome from 64, so he could well have met Lucillius and begun tinkering with epigram around that time. Certainly Martial’s own Book One is at pains to put distance between the new material and his various unspecified juvenilia.

Could some of Martial’s early poems have been in Greek? Epigram was fundamentally a Greek genre, and plenty of Romans were writing Greek epigrams before and after Martial’s time. Poem 9.332, included on your handout, is an inscriptional example by a good, second-century amateur poet with a demanding day job.

Regardless of Marcus’s real identity, or of whether Marcus had a real identity, the scenario presented by Lucillius’s two poems is already satisfyingly messy. They give us a Greek poet, with a Roman name, living in Rome, where he makes fun of another Roman-named and presumptively Latin-speaking poet, who composes epitaphs in Greek — including one for a boy with a Roman name, who comes from the Greek East.

And that’s assuming we don’t take ‘Κλαύσατε δωδεκέτη Μάξιμον ἐξ Ἐφέσου’ and the rest as a presumptive translation by Lucillius into Greek of an epitaph that Marcus has composed in Latin …but that is probably a complication too far.

STRATO OF SARDIS

I’ll end with a prolific and witty poet whose assigned period wanders in between the Hellenistic era and late antiquity, though as often as not, he is placed under Hadrian for no really good reason. Strato of Sardis specialised in pederastic verse, and the twelfth book of the Anthology comes down to us under what was probably the title he gave his own poetry-book, the Mousa Paidikē or Boyish Muse. I’ve given you two of his poems.

In the first, he complains to a friend that all the best boys are off-limits, by virtue of their Roman citizenship, which by his time I take to have been pretty widespread. Strato is nostalgic for the ancient ideal of a respectable love-affair in which the lover and his youthful beloved are of equally high social and moral standing, but sardonically admits a less idealistic and often mercenary contemporary sexual reality, closely aligned to Martial’s own pederastic verse.

Of course, 12.185 doesn’t at all imply this Lydian Greek poet was in Rome, or that he ever came west at all. There will have been plenty of purple-togaed boys in Sardis, I am sure.

But 12.254 suggests to me not only that he came to Rome, but that he was there in Martial’s day. Kathleen Coleman has observed that Martial seems to allude to Strato’s Boyish Muse, and I badly want them to have known each other — so much so that I’m half-tempted to write novels in which they team up to fight crime or hunt werewolves.

You will see that Strato 12.254 has a lot in common with Martial 9.36. Both poems elaborately flatter a wealthy and powerful figure who possesses a great and shining host of divinely beautiful young men: Erōtes, Strato calls them. This makes their master at least the equal of Zeus or Jupiter, who for all his power can claim only one such Ganymede. For Martial, the lord of heaven is merely ‘the other Jupiter’, whose power can surely be no greater and is less immediately felt than that of his earthly counterpart.

The identity of Martial’s ‘Ausonian page’ has never been in doubt; his epigram comes as the climax of a concentrated cycle of poems celebrating the beauty of Earinus, the handsome young favourite of the Emperor Domitian. For my part I am pretty confident that Strato is angling for patronage right alongside him.

In any case, the pairing of Strato and Martial feels like a good way to end in the context of MAPPOLA — Greek and Latin poets working in the same spaces, chasing the same kinds of outcome, and becoming hard to tell apart. I hope you’ve enjoyed our little tour of the Anthology, and I thank you for your time.