Epigram of the month: A (slightly belated, but heartfelt) Happy New Year, right after Blue Monday!

When the excitement of the New Year’s Eve with its squeals of happiness and colourful fireworks is finally over, when all the various superstitious rituals, in accordance with local customs and habits, have been carried out, and when the last bottle of sparkling wine has been emptied, a grey, cold, and somewhat miserable day – at least in this part of the world – follows. Sleepiness clashes with intention of getting up early in the morning and, in accordance with one’s new year resolutions, to go for a run in the park.

‘So, what is the point of wishing a Happy New Year,’ I have always wondered, all the while of avoiding to send cheerful messages.

This year feels different, though.

The last 12 months have been a challenge to, and meant significant change for, all of us – in terms of our perception of life and of other people.

Consequently also the wishes which I receive and make sound different from usual. They have lost that patina of clichéd phrases which used to annoy me before so much, and they have become more concrete and, ultimately, honest. Now, when I wish someone a Happy New Year, I really mean “I wish you, with all my heart, to be healthy, to spend plenty of serene days, and to be able to leave behind the hard times that you must have been through”.

And that is the reason why I am not going to give up opening the messages I send with New Year wishes. Not yet.

Actually, this year I have the desire to extend my special wishes to all carminatores and MAPPOLA fans out there, scattered around the globe, and I am going to do it with a jolly verse inscription, hoping that it will cheer you up on the day after Blue Monday.

The epigram that I have chosen for January 2021 is in fact different from the ones we have seen so far.

This month’s Epigram of the Month is engraved on a so called “oggetto parlante”, a speaking object.

In the Roman world literally everything was inscribed, and people used to write all sorts of things on everyday objects: they asserted their ownership on them, they declared their love, they wrote down their thoughts, and, of course, they made wishes.

Wishes – even Happy New Year ones – are found on Roman bottles and cups, for examples, viz. the typical receptacles for wine. Therefore, they carried phrases related to drinking and conviviality. As the surface available for writing was often very limited, the respective texts are usually fairly short, but nonetheless open to poetic inspiration or wordplays.

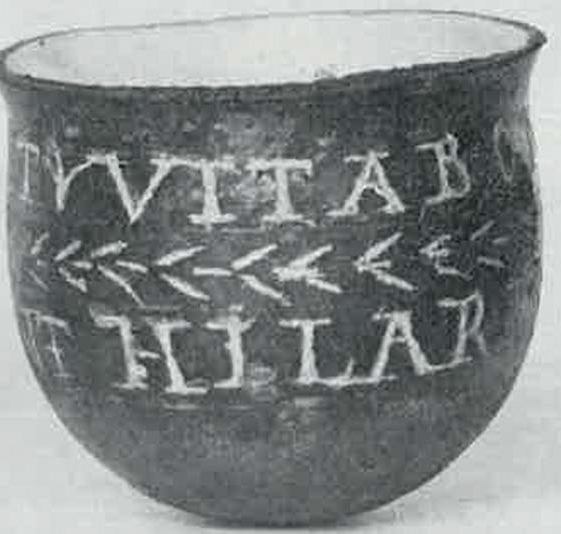

The artefact that caught my attention especially is a very small spherical glass beaker, only 4,8 cm in diameter.

CIL XIII 10025,208. Photo: F. Fremersdorf, Die römischen Gläser mit Schliff, Bemalung und Goldauflagen aus Köln, Cologne 1967, pl. 40.

This small and fragile inscribed object comes from Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippensium, today the city of Cologne, in Germany, which in Roman times was one of the major centres of glass production.

Vessels, glasses, ointment vials, and dishes were crafted in the numerous workshops of the city. They came in all shapes and forms, from the simplest bottles to technically elaborated vessels such as cage cups (diatreta), produced for well-off elite customers. Many of these objects are preserved at the Römisch-Germanisches Museum in Cologne, and only a few years ago they were displayed in a special exhibition Zerbrechlicher Luxus (‘Fragile Luxury’).

The inscription of the cup in question runs centrally around the beaker’s outer wall in two lines, and it reads as follows:

Vita(m) bona(m): vive bene et

hilaris propina parente (i. e. parenti).

A good life! Live well and

cheerfully drink to the health of the parent.

(CIL XIII 10025.208; F. Fremersdorf, Die römischen Gläser mit Schliff, Bemalung und Goldauflagen aus Köln, Cologne 1967, 74, no. 293 with plate 40 = EDCS-37700324)

The text, though arranged in two lines that are separated by a decoration that runs around the vessel’s entire waist, forms a single verse, namely in the shape of a composition that resembles a (slightly irregular) dactylic hexameter . The line break in the text’s arrangement coincides with a notional penthemimeral caesura.

Overall, the structure of the hexameter is quite regular, with the apparent exception of the verse’s first metrum, where there is one syllable too much. This irregularity is linked to a content-related repetition in the first line, where two words – the adjective bona (good) and the adverb bene (well) – would appear essentially to convey the same meaning.

Reading the inscription, I could not help but think, however, that the word vive (‘live!’) to a Roman ear would have sounded very similar, if not exactly identical, to bibe (‘drink!’) – and of course this text would have been read out aloud, as common, by its readers, for everyone around them to here. The similarity in the pronunciation of B/V is the effect of a linguistic phaenomenon called betacism (which is well documented for the Latin language). As a result of this, not only the phonetics, but also the very meaning of the two words may have been perceived by some Latin speakers as deeply connected.

The same two verbs, bibere and vivere, appear, for example, closely linked, on another famous cage cup from Novara (Italy), now preserved at the Museo Archeologico di Milano, a real masterpiece of fourth-century glass production, which is worth mentioning here.

Its inscription reads:

Bibe, vivas multis annis!

Drink, may you live for many years!

(Pais 1083,2 = EDCS-32100134)

The second part of the inscription of our much humbler beaker from Cologne explains to whom the very glass itself ought to be raised: hilaris propina parente (with a non-standard spelling of the dative).

If we take into account that this beaker was not a cup for everyday use (after all it is not New Year every day!), we might imagine, for example, that it was given to its owner as a gift.

Inscribed small vessels and beakers which were not for every day use like this one may have been very similar to the mugs with inspired, sometimes even funny, sentiments that to the present day we give away as gifts on special occasions, and whose messages (arguably) somehow fit their recipients (or aptly comment on the relationship between giver and recipient of the gift).

In fact, I have a couple of those items on my desk myself.

One, received by one of my best friends, carries the phrase “Today is a good day to smile” (cheer up, Chiara!), the other one, a present of a colleague, reads: “My job is also a kind of jungle quest” (and this is true sometimes).

Exactly like my own mugs, the messages on Roman glass tableware may have been personalised in order to meet to the needs of a variety of customers.

So, if, say, a young Roman, living at the frontier of a province such as Germania inferior entertained the thought to surprise his lover with a gift, rather than a beaker to celebrate mum and dad on occasion of New Year’s Day, he might have bought a more elaborate vessel with a representation of Neptunus amidst sea creatures and an inscription that read ––

Propino amantibus

I drink to the health of the lovers!

(CIL XIII 10025.204 = EDCS-75000273)

I am very much struck by the paradox that such messages wishing strength, health, and long life are written on thin and fragile glass, so as to show, perhaps, that, despite of all the sincerest wishes and lucky charms, life is a flimsy thing, which has to be enjoyed to the fullest and always be handled with care.

With the Romans who wrote these lines, I – and all of us here at Team MAPPOLA – would like to raise our glasses (or tea cups), virtually, and drink to your health in 2021!