Epigram of the month: But Is It Art?

In the November edition of our recently launched Epigram of the Month series, Alexander Gangoly pointed out the very special relationship of the people of Vienna with their cemeteries.

Vienna’s most famous cemetery, the Vienna Central Cemetery, is not only the subject of songs but also of several TV documentaries.

The Cemetery for the Nameless, where Peter Kruschwitz found some interesting modern epigrams, is considered a hidden gem among tourists.

And then there are those cemeteries that are, although rather less well known, popular weekend-destinations for residents…!

Vienna’s Hernals cemetery, for example, as well as the adjacent Dornbach cemetery are much loved for their sunny hillside locations and the stunning views they provide over Vienna’s 17th district. A few benches by the upper cemetery wall are regularly in high demand by those who desire a peaceful and quiet setting for their reading the Sunday papers: curiously, not everyone is an epigraphist, coming to a graveyard to read the stones…

While monumental family graves near the main gate at the foot of the hill of these cemeteries commemorate the wealth of the privateers and house owners (or privateers’ and house owners’ wives!) of the late 19th century, reading the Sunday newspaper at the top of the hill one finds oneself in the company of simpler and also newer graves.

The inscriptions related to those simpler and more recent burials typically only mention the names of the deceased alongside their dates of birth and death. The further one moves away from the graves of the (urban) elite, the rarer it is to encounter any personal information related to the deceased and the lives they led – such as their profession or their family ties. (Of course, as always, exceptions prove the rule!)

Strikingly, this lack of provision of personal information in the inscriptions of the hoi polloi is the very opposite of what one frequently encounters in the study of ancient Latin funerary inscriptions: here, more often than not, precisely those funerary inscriptions for people of lower social classes are the ones yield copious amounts of interesting biographical detail.

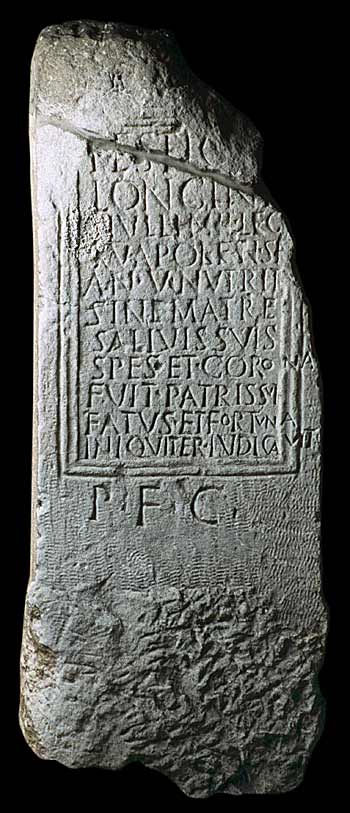

A most remarkable example in that regard is an inscription from Carnuntum in the province of Pannonia superior, which was put up by a father for his little son. (AE 1936.67 = EDH 24324 = Lupa 4437).

The monument in question was discoverd in 1932, alongside other funerary monuments, in the context of excavations conducted in the area of Carnuntum’s legionary cemetery. The piece belongs to a period from A. D. 71 to A. D. 114, when the legio XV Apollinaris, which is mentioned in the text, was stationed in Carnuntum for its second time. The upper part of the stone is damaged, but the text has remained legible in its entirety, bar one or two letters in the first line. Eleven lines of text are placed inside a frame, albeit spilling over the right margin of the framed area occasionally. A twelfth line, at the very bottom, was placed underneath – and outside – the framed area that was designed to display the inscription.

The text of this inscription reads – and translates – as follows:

Festio [-]

Longini

Iulli mil(itis) leg(ionis)

XV Apol(linaris) f(ilius) h(ic) s(itus) e(st)

an(norum) V nutritu[s]

sine matre

salivis suis

spes et corona

fuit patris sui

Fatus et Fortuna

iniquiter iudicavit

p(ater) f(aciendum) c(uravit)

Festio, son of [-] Longin(i)us Iullus, a soldier of legio XV Apollinaris, lies here at an age of 5 years. Without a mother, fed on his own saliva, he was his father’s hope and crown. Fatus and Fortuna passed an unjust sentence. The father has arranged for the execution (sc. of this monument).

The first four-and-a-half lines, as well as the postscript that is line 12, outside the framed field, assemble all the most important key data: a child named Festio was buried here, who died at the age of (approximately) five years. His father, one [-] Longin(i)us Iullus, was a soldier of the legio XV Apollinaris, and he took care of this burial’s execution.

All the requirements for a funerary inscription would have been perfectly met with this information already.

The father decided, however, to express the tragedy of his child’s death and his pain by having another passage engraved, and to do so in very personal words. In the middle of line 5, the tone and style of the inscription changes. The formulaic prescript is followed by ––– yes, what exactly is it?

An epigram?

It is first and foremost a deeply emotional text.

Longin(i)us Iullus lived through probably the worst nightmare of all parents: he had to bury his his own child.

The inscription tells us that little Festio did not have an easy start to his life because, apparently, he grew up without a mother. We do not know anything about her fate, apart from her absence (sine matre), but we can assume that she accompanied Longin(i)us Iullus in the military convoy and – presumably – died in childbirth.

The tragic extent of this situation is shown to the reader through a passage that employs a truly breathtaking and unique imagery: nutritus sine matre salivis suis, ‘without a mother, fed on his own saliva’. Festio was not able to drink from his mother’s breast as other children do. Yet, he survived infancy, and he was his father’s pride and joy (spes et corona!). Alas, father and son did not get to spend many years together. Festio died young, still in his early childhood. In the end, his father could do nothing but state that Fate, personified, Fatus and Fortuna, had ruled unjustly.

Back to the question: Is it an epigram?

When Peter Kruschwitz, in a recent lecture on “The Roman verse inscriptions of Carnuntum“, showed the inscription for Festio next to the other funerary epigrams from Carnuntum, the answer of some members of the audience was clear: the inscription is not metrical, therefore it cannot be an epigram.

Still, it is an inscription with peculiarities in style and content, evokes emotions and seems to make use of a poetic language. One that is strongly reminiscent of a group of Latin funeral epigrams in which the death of children is mourned.

So, is the answer really that clear?

What constitutes an epigram? Where do we draw the line between “real” epigrams and epigram-inspired (or rhythmic) inscriptions?

And, importantly for us here at the MAPPOLA project, what do you expect to find in a database on the poetic landscape(s) of the Roman Empire…?

Soon, we will issue a call for papers and posters for a workshop, to be held in the autumn of 2021, inviting you further to discuss this important question with us!