Filling a void, or: Celebrating Black History Month

Diversity and inclusion, in conjunction with an interest in regional variation and change, are aspects that are at the heart of the MAPPOLA project and its research into the poetic culture of the Roman Empire: this affects social structures, sex and gender, religions, and languages just as much as it touches upon race and ethnicity.

October 1st, 2020, does not only mark MAPPOLA’s first birthday (how did we laugh when the ERC requested we filled in a risk register in 2019, to explain our responses to risks such as global disasters….!).

October 1st is also the first day of a month that in many contexts is celebrated as Black History Month. So here is a little piece to provide food for thought on that occasion.

Representations of, and explicit references to, black people are scarce in the Roman verse inscriptions. I have talked about one rare example on my private blog a while ago (follow this link, if you are interested).

But there may – may! – be another case, and that one is both highly symbolic for, and particularly fascinating with a view to, Black History as a matter of giving visibility and a voice to black people in all human communities.

The text in question is a poem inscribed on the Colossi of Memnon at the necropolis of Thebes (near modern-day Luxor) in Egypt.

These colossal statues had become a tourist attraction already in the ancient world, and to the present day they are covered with ancient graffiti, some of which in verse. (This is beautifully documented on the twitter feed of Following Trajan here.)

Following an earthquake, one of the statues had developed signs of substantial structural damage, and related to this is the remarkable sensation of the statue producing a distinctive sound – giving colossal Memnon (represented with the face of Amenhotep III, the father of Akhenaten).

The phenomenon is mentioned in a number of inscriptions found on the colossus, including the following one (CIL III 55 = CLE 272; you can spot parts of it on the photo published here, in the top right corner.):

Memnonis [- – -]

clarumque sonor[em]

exanimi inanimem mi[ssum]

de tegmine bruto

auribus ipse meis cepi

sumsique canorum

praefectus Gallorum al[ae]

praefectus item Ber(enices)

Caesellius Quinti f[il(ius)]

A Barmo[- – -]. (or: A Bararo?)

Most of the text, slightly damaged, is easily understood and, where necessary, restored. The final line remains unexplained. What is fascinating, however, is the first line.

Already in its present state, this piece attributes a remarkable voice to an African individual. Here is how Edward Courtney translated the piece:

I myself absorbed and took in with my own ears the voice of Memnon and the distinct harmonious sound, animate though emitted from an insensible, inanimate surface – I, Caesellius (Abararo?) , son of Quintus, prefect of the troop of Gauls and prefect of Beronice.

What is missing, and this is where it gets really interesting, is the damaged end of the first line. Several proposals were made to restore the text here, all equally problematic to an extent. The most credible attempt at healing the text, however, was proposed by Alfonso Traina:

Memnonis [Aethiopis uocem] etc.

I myself absorbed and took in with my own ears the voice of Aethiopian Memnon and the distinct harmonious sound, animate though emitted from an insensible, inanimate surface – I, Caesellius (Abararo?) , son of Quintus, prefect of the troop of Gauls and prefect of Beronice.

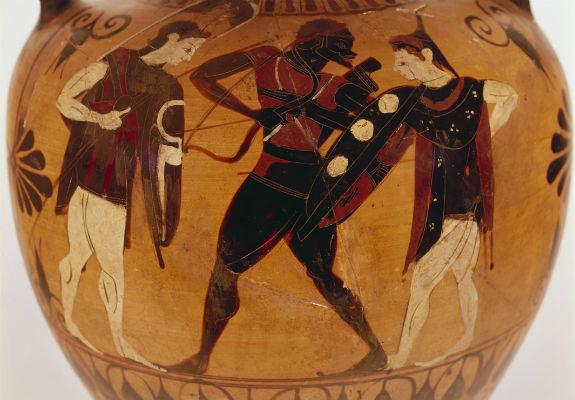

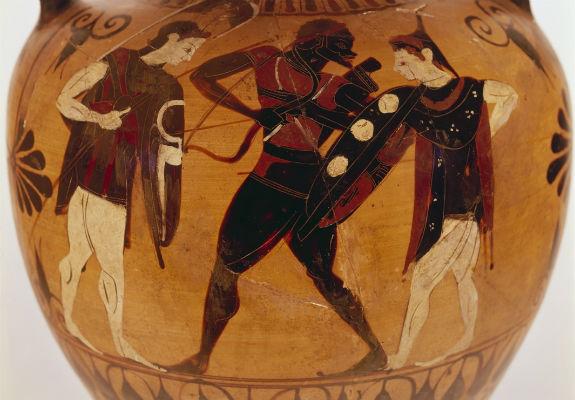

Traina’s tentative addition is based on a line in Catullus (and multiple further instances) in which Memnon is specifically labelled as Aethiopian (‘the ones of the burnt faces’, literally), or in which he is simply called ‘black’ (niger), related to the myth of Memnon that has him as a king of the Aethiopians, represented as a black man in ancient visual representations such as this vase painting:

Without question, the structural damage to the colossus will always leave an element of doubt to the restoration of the text. Traina’s proposal is appealing as it aligns itself with a long textual tradition in the history of Roman poetry.

If Traina’s view, that the void is to be filled with a reference to an indisputably black people of the ancient world, is correct, however, this would – quite literally – restore a voice to a black individual, whose mythical power was harnessed by, as well as represented through the addition of the face of, the Egyptian ruler Amenhotep III.

It is an extraordinary case of transculturalism as well as empowerment, bursting forth from the poetic (written) reflection on the soundscape of Egyptian Thebes, in which a Roman, writing in Latin, yet commanding a unit of Gauls, celebrated his touristic encounter with a myth of the Greek world, related to Aethiopia, as he understood it to be reflected in an ancient Egyptian monument.

Diversity may be confusing at times. But it certainly is not boring, and it makes all our lives richer for it.