Guest blog: Strangers in a strange city

Davide Massimo writes about his work and time at Vienna, where he was a visiting researcher of Team MAPPOLA in February and March 2022, enabled by kind support of Österreichischer Austauschdienst (ÖAD):

I have been a ‘stranger in a strange land’ since I left my home country (Italy) in 2017 to pursue a doctoral degree in the United Kingdom. This was barely one year after the ominous date of 23rd June 2016, i.e. the date of the Brexit referendum, which meant that the country I was moving to was only destined to become stranger and stranger, and probably not for the best. I have lived in Oxford, UK, since 2017; I like to think I am now less of a stranger (whenever that is convenient, of course). This means that I forgot what it means to move to another city for a longer period of time; and that is why the prospect of coming to Vienna in 2022 for a more extended research stay was both exciting and scary.

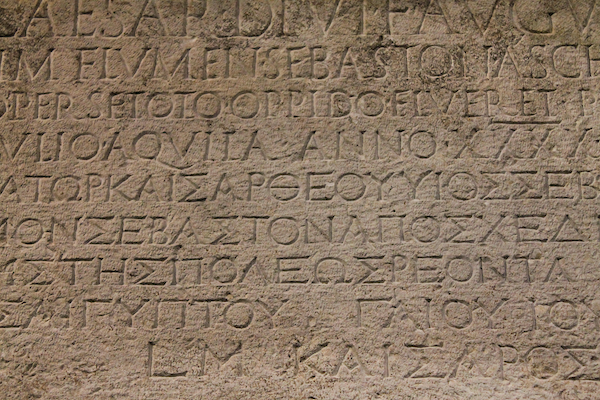

It is a fortuitous circumstance that my research also revolved around strangers in strange land(s). My doctoral dissertation was devoted to the Hellenistic poet Leonidas of Tarentum, who famously laments in a (presumably) fictitious self-epitaph that he died in a strange country (Anthologia Palatina 7.715, ll. 1-2 Far from the Italian land I lie, and from Tarentum, / my homeland, and this is bitterer than death to me). As it often happens, while working on so-called ‘literary epigrams’ I also got interested in epigraphic epigrams, i.e. poems transmitted on stone. I thought (and still think) that these do not usually get the attention they deserve and so I set out to give them some. As a first ground of exploration, for a number of reasons, I chose the Greek inscriptions from the city of Rome, of which ca. 1,700 survive (among these, ca. 350 are poetic texts – the ones that interest me more).

This took me, unsurprisingly, to Rome (or rather back to Rome, which happens to be my birthplace), where I started my research thanks to the generous support of the British School at Rome. When I was there, part of my research schedule entailed trying to have a look at some of the actual inscribed stones. Even though some of them ended up in strange places (and there is actually one in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford), most of them are in Rome. They are scattered among museums (few on display, most in storerooms), ville and palazzi which belonged to the Roman nobility.

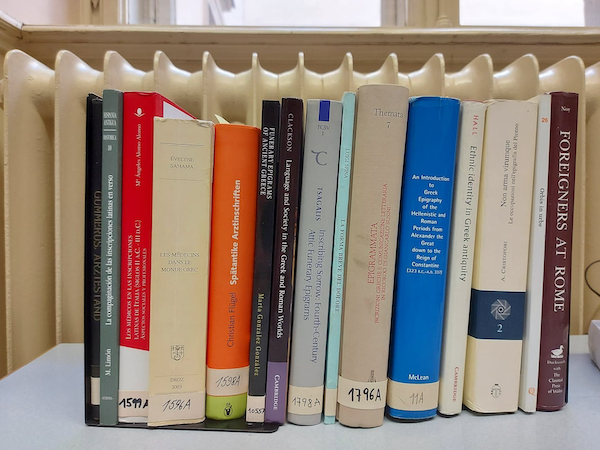

In 2022, then, the second act of this research project took me to Vienna, where MAPPOLA was kind enough to host me at the ‘Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik’ of the University of Vienna. I did not start off as an epigraphist, so in a way I was again a bit of a stranger; but as it happens when you are thrown into terres inconnues, I did learn a lot.

As a ‘literary person’ my main interest in the funerary poems in Greek that come from Rome is in their literary strategies, their poetic style, and their language. But these texts are first and foremost a historical testimony, as they record the presence of Greeks in the Urbs. The interaction of Greek and Roman culture has been the subject of much academic research; the famous line of Horace, Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit (‘conquered Greece conquered its fierce victor’) has been often used to summarise the process through which Greek culture, though belonging to a world that was subdued by the rising power of Rome, enthralled Roman culture – and in a way, had its revenge. In other words, Greek lost on the battlefield, but got the upper hand through other means.

The story of this interaction, however, is of course much more complex. Who were the Greeks that physically came to Rome – and died there, leaving their memory on stone? An important premise is due. When we say ‘Greeks’, we should rather say ‘Hellenophones’. By the time Rome had started meddling with the Greek world, in fact, Greek language and culture had already spread far beyond mainland Greece through the conquests of Alexander the Great. Greek was then a key linguistic and cultural component of all the Hellenistic kingdoms, which included territories as diverse as Egypt and Syria. Greek-speaking foreigners coming from mainland Greece were actually just a part of the Greek-speaking foreigners in Rome.

As for the motive of the migration, well, not everybody had a choice. The rich spoils of war that the Romans took with them after conquering Greece and other areas of the Mediterranean did not only consist of pretty artworks, but also of Greek-speaking slaves. Other individuals of free conditions willingly decided to come to Rome because of the job opportunities that their origin offered especially compared to their now subjugated countries of origin (what is often called ‘push factors’ by scholars of migrations). They were – or became – merchants, teachers, doctors, artisans, artists, and entertainers.

In any society, migrants always encounter resistance. Literary sources often represent feelings of xenophobia towards these Hellenophones. One only needs to think of Juvenal’s invectives (Sat. 3.60-61, 74-78, transl. S.M. Braund):

… non possum ferre, Quirites,

Graecam Vrbem. quamvis quota portio faecis Achaei?

[…]

… ede quid illum

esse velis. quemvis hominem secum attulit ad nos:

grammaticus, rhetor, geometres, pictor, aliptes,

augur, schoenobates, medicus, magus, omnia novit

Graeculus esuriens: in caelum iusseris ibit.

I cannot stand a Greekified Rome. Yet how few of our dregs are Achaeans? (…) Say what you want him [scil. a Greek] to be. In his own person he has brought anyone you like: school teacher, rhetorician, geometrician, painter, masseur, prophet, funambulist, physician, magician—your hungry Greekling has every talent. Tell him to go to heaven and he will.

Greek inscriptions from Rome, on the other hand, often give us the ‘migrant perspective’. Let us look at this funerary inscription from a sculptor coming from Aphrodisia, in Asia Minor (IGUR 1222):

I, Zeno, came from the most blessed Aphrodisia:

Having been to many cities, respected for my arts,

And having built for my son Zeno, child who died young,

A tomb and a stele, I sculpted the images myself,

Having worked with my own hands the noble work.

Here I had built the tomb for my dear wife Kleine and

My dear son, and after having lived four cycles of ten years,

We now lie here, speechless, having lost our lives,

My child, my wife and I, famous for my works.

One wonders whether Juvenal and like-minded people ever read this kind of inscriptions (just like one wonders today with many xenophobes whether they even pause and think about the life of migrants in a world that is as turbulent than that of 2,000 years ago, if not more).

One of the professions for which Greeks were renowned was the medical art, given their long-standing tradition and learning in this practice. The coming of Greek doctors was not exactly welcomed at the beginning. Cato the Elder seems to have thought that ‘[Greek doctors] have conspired among themselves to murder all barbarians with their medicine; a profession which they exercise for lucre, in order that they may win our confidence, and dispatch us all the more easily’ (according to the testimony of Pliny the Elder, Nat. Hist. 29.7, transl. J. Bockton). But we know that the migration flow only increased. To the point that, according to Suetonius (Caes. 42), Caesar granted roman citizenship to Greek doctors to keep them in Rome. Most of the doctors of the imperial family in the following centuries, after all, were Greeks. In this case too, inscriptions tell us of specific individuals and some of their life circumstances. Many of these inscriptions praise the art of these professionals, whose learning contributed to save lives (IGUR 1309):

Here lies Pompeus Diocles, worth as many other men,

who held the highest limits of wisdom.

In this case, the deceased is glorified by an learned literary allusion which tells us that he was a doctor. The first line, in fact, borrows part of a Homeric line (Iliad 11.514 ἀνὴρ πολλῶν ἀντάξιος ἄλλων) which refers to Machaon, son of Asclepius and legendary warrior-doctor of the Acheans.

On other occasions, we learn about the families of these doctors (IGUR 1349):

The old world knew a honourable Penelope, and this one

Has a honourable Felicitas, probably not less so:

from her, you daimon, often heard that she prayed

she would die before her husband.

Then listen to my voice too, Pluto,

as I pray, if I go to Hades,

to find my Felicitas with you.

The doctor Claudius Agathinus set up this portrait of Felicitas, witness of temperance.

In front of grief and loss, their profession of Claudius Agathinus fades in the background, and there is no praise of his art. We get to see the man behind the doctor. This is not surprising, as one would expect a person whose profession is to save people to be all the more heartbroken in front of the inevitability of death. This is possibly alluded to in an inscription set up by his relatives to commemorate the doctor Nicomedes (IGUR 1283, having saved many with his anodyne medicines, and now, dead, has a painless body, φαρμάκοις ἀνωδύνοις ἀνώδυνον τὸ σῶμα).

As we said, many Greeks animated the cultural life of the Roman empire as musicians, poets, and entertainers. Even though we know some Greek authors of the Imperial age, there is a countless amount of poets who are destined to remain just names for us. Occasionally, inscriptions give us some glimpses of this. This is the case of a certain Petronia Musa, commemorated by an inscribed funerary altar now in Villa Borghese, Rome. We do not actually know whether she was Greek, but it is very likely that she composed poetry in Greek; at any rate, it is of some significance that her epitaph was written in Greek.

The text reads (IGUR 1305):

The dark-eyed Muse, a sweet singing nightingale,

now suddenly silent, is held by this modest tomb.

And this stone, clever and famed like her, lies here:

o beautiful Muse, may this ash be light for you.

What evil, evil spirit took away my Siren,

who took my sweet little nightingale,

in just one night, destroyed by cold drops?

O Muse, you died, your eyes were undone,

and your golden mouth was shut: and in you

not a remnant of beauty, of wisdom remains.

Go to waste, terrible pains; ill-fated men are devoid of bright hope.

All the things governed by fate are obscure.

Of the poetry (and possibly music) of Petronia Musa, all we have left are these words of praise. What was her best ability cannot by conveyed by the silent stone, as duly noted by the nameless speaking voice of her epitaph (perhaps her husband?).

There is still much work to do on this material (and MAPPOLA is certainly making a great contribution in this direction). I am glad I had the chance through my stay in Vienna to delve further into this research. As former capital of an empire which included people speaking Germanic, Slavic and Romance languages it is a great place to reflect on mobility, migration, and encounters of different cultures; and as a place which was at the centre of a global conflict ca. 70 years ago, it has known its share of displacement. To this day, it is still at the crossroads of Mitteleuropa and somewhat like the Urbs attracts migrants of different kinds: both the ones that willingly decide to move here and others that have no choice left. Towards the end of my Austrian stay, a new wave of refugees has been arriving in the city in light of recent events, a scenario that happened over and over again in the past couple of decades. Historians and classicists are bound to wonder how much of the history that we live through is going to be lost in time: few things are as durable as stones, after all, and these seem to have become quite out of fashion.

Acknowledgement

I wish to acknowledge the support provided to my research by the British School at Rome (through a Rome award, September—December 2021) and the OeAD (through an Ernst Mach Worldwide Grant, February—March 2022) as well as by the University of Vienna and all members of the MAPPOLA Team.