Epigram of the Month: Staring into the void

It is well known that high child (and especially infant) mortality was a fact of life in antiquity. The omnipresence of this common experience did not, however, lessen the pains felt by individuals when confronted with this deeply traumatic experience. To the contrary, there is substantial evidence to refute any notion of parents being uncaring and not suffering, profoundly, when their children died.

In some cases, they could barely cope with their grief, as was the case for Herodes Atticus when he lost his son. From the correspondence between Marcus Aurelius and Fronto we find out that Herodes could not bear the death of his son calmly (non aequo animo) and encouraged him to write a letter of consolation.

Herodi filius natus <hodi>e mortuus est. Id Herodes non aequo animo fert. Volo ut illi aliquid quod ad hanc rem adtineat pauculorum verborum scribas. Semper vale.

The son of Herodes, born to day, is dead. Herodes is overwhelmed with grief at his loss. I wish you would write him quite a short letter appropriate to the occasion. Fare ever well.

Fronto, Correspondence, I.7, Translated by C. R. Haines. Loeb Classical Library 112. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919.

Funerary poems, the main focus of our research here at the MAPPOLA project, provide us with an unparallelled and rich resource towards recovering and understanding the emotions of parents who lost their children.

There are many instances in which inscriptions were combined with sculptures to represent the children. In many cases, the children were not realistically portrayed. They were depicted as rather older than the age stated in the text, associated with mythological or divine figures, gaining immortality in this way, even though they were evidently very mortal. Where children were not represented in divine guise, they often show different attributes to reflect their professional promise (e.g. as orators, soldiers, females – intellectual accomplishments or their domestic qualities).

For this month’s epigram I would like to present to you a funerary monument from Bursa (Prusa ad Olympum, in the province of Bithynia), erected by one Leukos for his little girl.

One might say that there is nothing special about this monument, at least at first glance.

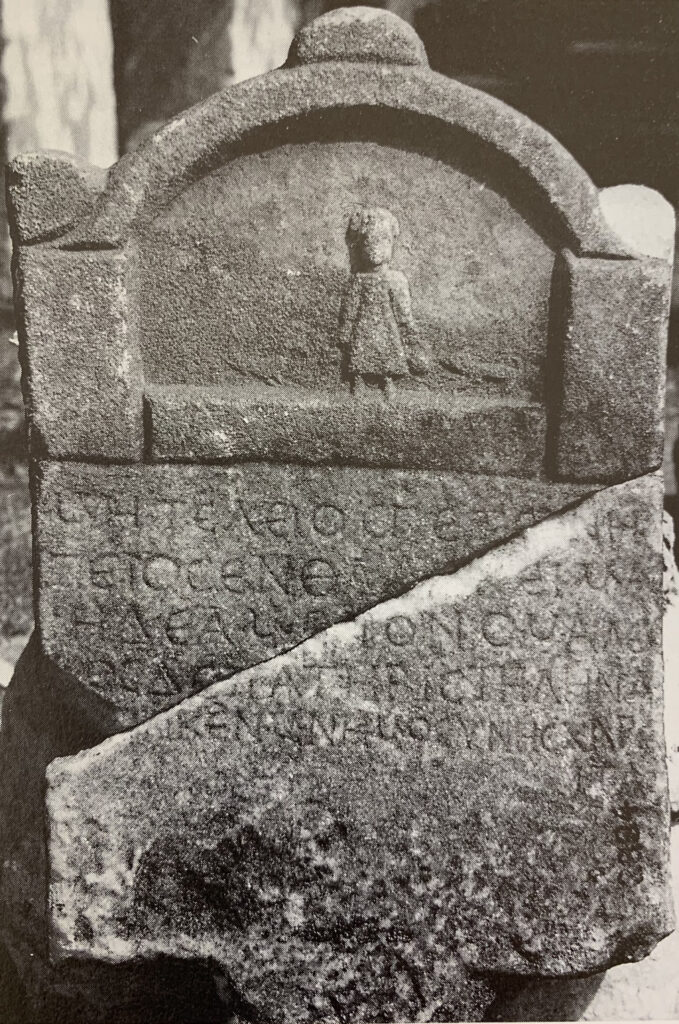

It is a marble stele (61 x 38 x 5 cm) with an arched pediment with three round acroters. The sculpture represents a very little girl wearing a long garment and holding unidentified objects in either hand. The girl is accompanied by two animals: on the right, there is a little dog, and on the left, there is a bird (or, less likely, another dog?).

The monument’s inscription (SGO 09/04/09) reads and translates as follow:

μὴ τέλειος γ’ ἔτει νή|πειος ἐνθάδε κεῖμα|ι·

Ἡδέα μὲν ὄνομα, Λεῦ|κος δὲ πατὴρ

ἰστήλην ἀ|νέθηκεν μνημοσύνης χάρε|ιτα.

Not as an adult, but still as an infant I lie here;

Hedea was my name; Leukos, my father,

erected this stele in remembrance.

IK 39 Prusa ad Olympum 57. Photo: Pfuhl – Möbius, Die ostgriechischen Grabreliefs, I, Tafel CXIII, nr. 764.

From the three verses we find out that Hedeia died too quickly, without having had any opportunity to gain any life achievements.

The text outlines important stages of human life, from our shared beginnings as a νήπιος (= baby; literally: ‘not (yet) speaking’) to our (unfortunately not always shared) experience that is our coming of age as a τέλειος (= grown-up, literally: ‘someone who has reached the finish-line of reaching adulthood’).

Hedeia, ‘Sweetie’ (as her name translates into English), was still to disover her place in life – she was not an adult, and she was barely a baby, in between all imaginable stages of life, in a void.

And in the same way, I feel, her iconographic representation uniquely reveals this haunting truth: a little girl, without parents, only a couple of companion animals, in a wide, empty space, a void. There is nothing there to change that reality, nothing to reflect and represent what might have been. No deity to lend her their immortality by association.

The humble, simple language of the epitaph, in conjunction with this haunting depiction of the girl, when closely analysed, make palpable the emotions felt by the father and transmit them onto the monument’s readers and beholders.

A very small girl, with no prospects, and all alone.

This is pure sadness, and one wonders what there is left to say in order to ease that pain.

Is there anything more to say?

I do not know about you.

But every time when I look at the monument, I have this very vivid vision of a little girl, lost and alone on a meadow, who may or may not hold a balloon in her hands.