Sic mundus creatus est, or: Roman Highway to Hell

(by C. Cenati, V. González Berdús, D. Murzea)

The Romans did not carve lanterns out of pumpkins, most likely, but nonetheless they had their own way of celebrating Halloween, and not just once a year, but at least three times (August 24th, October 5th and November 8th). On these days the underworld came in communication with the upper world. This happened through the Mundus Cereris, a gate to the underworld situated in the Forum Romanum.

The Mundus was a round pit, whose form was imagined to replicate the dome of the sky; it was always covered by the lapis manalis, a stone named after the Spirits of the Departed, the Manes, with the exception of those three days when the passage was opened (Mundus patet) – if you are a Netflix addicted like us and you have watched Dark the phrase sic mundus creatus est becomes suddenly clear…

Are three Halloweens more than enough?

Of course not.

The Di Manes played a very important role in the Roman religion, and, as a consequence, the Roman calendar included plenty of festivities to remember, honour and placate the Spirits of the Underworld. During the Parentalia (13–22 February) the family met at the graves of their deceased relatives and offered sacrifices. In May, during the Lemuria, the pater familias offered beans to the unburied dead (Lemures) who were considered dangerous for the living.

Why beans, you may ask?

Well, it’s not very clear, but a particularly entertaining theory (by A. Delatte, referenced in F. Cumont, Lux Perpetua (1931), 397) suggests that beans were thought to contain the spirits of the deceased, set free through the flatulence they caused .

It is not a surprise that burial monuments are so strikingly present in the landscapes of Roman cities and that people used to set in stone the memory of friends and relatives providing – especially in verse inscriptions – details on their lives, characters, hobbies, joys and regrets. Often, this information was presented in the first person, as if the deceased, now part of the Manes and, therefore, a divinity, was directly addressing the reader.

In the cases we chose to present to you here, this resource is taken to its highest level, leaving us under the impression that someone is right there, waiting for our reaction – and that the mundus could, in fact, open at any moment.

Let’s share the thrill!

The first text we have selected could very well be read with the Parentalia in mind. It is the epitaph of one Marcus Porcius, from Obulco (modern day Porcuna), in the Baetica, and it can be dated to the first half of the first century A. D.:

M(arcus) Porcius M(arci) [- – -].

Heredibus mando etiam cinere ut m[eo uina subspargant ut super eum]

uolitet meus ebrius papilio. Ipsa ossa tegant he[rba et flores].

Si quis titulum ad mei nominis astiterit, dicat ‘[id quod reliquit]

auidus ignis quod corpore resoluto se uertit in fa[uillam bene quiescat]’.

Marcus Porcius, son of Marcus […] I also command my heirs to scatter wine on my ashes, so my drunk spirit can flutter above them like a butterfly. May grass and flowers cover my bones. If someone stands by the inscription of my name, may they say ‘may it rest blissfully what was left by a voracious fire, which, once the body was released, turned itself into ashes’.

(Translation: V. González Berdús)

Rather beautifully, Marcus speaks directly not only to his heirs, but also to whoever may have stopped to read his epitaph, and he gives instructions on how he would like to be honoured and remembered.

In the first case, he almost compels them not to be stingy when it comes to libations of wine. Through that, he suggests, his soul – here represented by a butterfly, papilio, that flutters around the monument) – would spend eternity in blissful tipsiness. We could, of course, also take a much more creepy approach to reading this text, however, as papilio may also denote a ‘moth’, and moths are undoubtedly connected with death and decomposition.

Just picture what impression the reader of this text might have got if, after their reading this inscription, they saw a moths fluttering around…!

It is a typical feature of Roman funerary inscriptions that they imagine the deceased directly to address passers-by, asking them to read out loud the message set on the stone. This way, the deceased were able to speak again through the voice of the readers: and it is hard to imagine that this could have happened without a strong emotional effect on the living.

In the first verses of our second inscription (CIL XI 627 = CLE 513, l. 1-6) from Forum Livii (today Forlì, in Italy) the text goes as far as giving the impression that a stranger who stops to read the text on the monument is literally possessed by Clodius Paulinus:

C(ai) Clodi Paulini

uix(it) ann(is) XXIIII, m(ensibus) VIII, d(iebus) X, h(oris) VIIII.

Carpis si qui [uia]s, paulum huc depone laborem.

Cur tantum proper(as)? Non est mora, dum leg(is): audi

lingua tua uiuum mitique tua uoce loquentem.

Oro libens, libens releg(as), ne taedio duc(as) amice.

[This is the monument of] Gaius Clodius Paulinus, who lived 24 years, 8 months, 10 days and 9 hours. If you have taken this path, leave it for a moment. If you there seize these ways, let go of the stress for a short while. Why such a rush? There is no time wasted while you read: listen to a living person who talks in your tongue and with your gentle voice. I ask you to read this favourably, favourably, so that you will not derive dislike, my friend.

(Translation: P. Kruschwitz)

Paulinus comes back to life every time that somebody reads his inscription. He borrows the body, tongue, and voice of the unwilling individual who happens to stop for a while in front of his funerary monument.

Creepy, isn’t it?

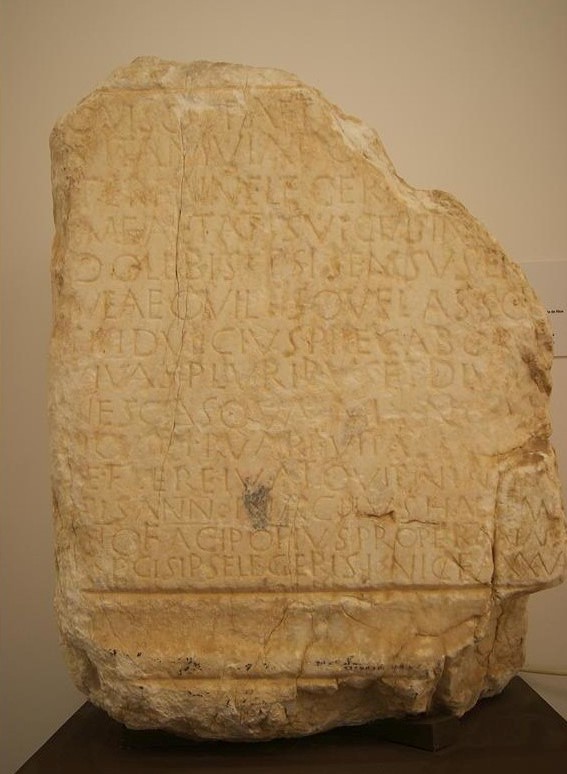

Last but not least, in a monument from Pax Iulia in Lusitania, modern day Beja (CIL II 59 = CLE 1553 HEp 2006.440 = AE 2006.564 = HEpOl 21142) the reader might have had the uncomfortable feeling of being observed, literally, by the young woman buried in the tomb:

Quisq(uis) praet[eris hic]

sitam, uiato[r, postquam]

termine legeri[s peremptam]

me aetatis uicesim[o]

dolebis. Etsi sensus er[it]

meae quietis qu(a)e lasso

tibi dulcius precabor.

uiuas pluribus et diu [se]-

nescas qua m[ihi non]

[l]icu[it] fruare uita [si]

[t]e flere iuuat quitn(i) inge[m]-

[i]scis ann[- – -] Inachus han[c] m[e]-

[ri]to fac(it). i, potius propera: nam

[tu] legis, ipse legeris: i! Nice a(nnos) XX u(ixit).

Whoever passes me by, as I lie here, traveller, you will feel pain [after] you have read that I [was snatched away] at my life’s twentieth boundary-marker.

Even though you will experience a sensation of my own rest, I will pray for a sweeter one for yourself, as you are weary. May you live for many years and grow older still for a long time: enjoy a life which I was denied. If you feel like crying, why don’t you start? […] years. Inachus had (this monument) made deservedly. Go! Nay: hurry! You read, you will be read yourself! Go! Nice lived 20 years.

(Translation: P. Kruschwitz)

Nice creates such a deep empathy with the traveller who is reading the verses, that they would be able to perceive the sensation of (aeternal) rest that pervades her and, conversely, she would feel the pain of the reader and his/her need to cry.

If you would like to experience this deep connection with Nice, you can still stop before her monument at the Evora Museum

So, even though Romans had their set dates in which the underworld came in touch with the world of the living, the truth is that Latin verse inscriptions grant us the same opportunity everyday. For us carminatores, mundus patet cotidie.

Happy Halloween from Team MAPPOLA!